In prison, having a cellmate you get along with is a rarity, but for Anthony Ehlers and James Scott, who have been cellmates for nearly five years at Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill, Illinois, they were one another’s family.

“He and I were a big odd couple to be best friends,” Ehlers, 48, wrote in a letter about Scott. “Guys used to make fun of us. We didn’t care. I’m sure it was kind of weird, he was a short, bald, dark-skinned Black guy, and I am tall, and very white. But, we were inseparable.”

In March, when Ehlers felt body aches, a sore throat, dry cough and a loss of smell and taste, he worried he had been infected with COVID-19, and worse, that Scott would get sick too. He was right.

While Ehlers survived the virus, Scott did not. On the night of March 29, Scott was transported to St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Joliet, about a 15-minute drive from Stateville, where he tested positive for COVID-19, Ehlers said. Though he didn’t know it at the time, Ehlers would never see Scott again.

Nearly a month later, on April 20, 58-year-old Scott died, records provided by the Illinois Department of Corrections show. Scott is among 12 Stateville inmates who have lost their lives as of May 18 to COVID-19, according to records obtained from IDOC. (IDOC recently denied a request for an updated total).

More than a month after Scott’s death, Ehlers remains in the cell they once shared together, only now, there’s a new cellmate in Scott’s place. Confined to his cell, Ehlers is left with his thoughts, and there’s one that he can’t seem to escape: the idea that he was responsible for getting Scott sick.

“There is such a big hole in my life right now,” wrote Ehlers, who has been at Stateville since 1996, serving a life sentence for a murder conviction. “I feel empty and alone … Did I kill my best friend?”

With no end in sight to COVID-19 and no way out, the men inside Stateville are at the center of the pandemic in Illinois. According to the IDOC website as of June 24, Stateville has had the most confirmed COVID-19 cases of any Illinois prison, with 188 incarcerated individuals infected, or 13% of its inmate population, as well as 79 staff members infected. East Moline, with 28 confirmed cases, is a distant second with nearly 3% of its inmate population infected.

In detailed letters and interviews, Ehlers and other Stateville inmates described conditions they say have facilitated the spread of the virus and the deaths of many inmates, even after officials placed the facility on lockdown on March 14 to try to contain it. With more than 1,100 men incarcerated at Stateville — many sharing a cell — social distancing is impossible, inmates have told the Reporter. That makes the need for cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment that much more important. But prisoners said they’ve received little to no PPE, cleaning supplies or proper medical treatment, and that they are regularly exposed to objects touched by others. Since the pandemic started, their access to the commissary has been limited, which has only made the situation worse, since it’s harder for the men inside to buy soap and other basic supplies to get by.

But a lack of supplies are only part of what inmates say they are facing. Several inmates also said IDOC is failing to isolate those who are infected, including by housing inmates who are not infected with those who have tested positive for COVID-19, are exhibiting symptoms consistent with the virus, or are awaiting test results.

According to IDOC spokesperson Lindsey Hess, the department is “appropriately quarantining or isolating men and women in custody, and equipping everyone who lives and works in our facilities with personal protective equipment.”

While many of the men inside Stateville are serving decades and even life in prison for serious crimes, some say COVID-19 has transformed their sentences into more severe punishments than were ever expected. As the outside world finds ways to socially distance, those in custody are stuck, feeling they are just waiting for the virus to reach them and facing conditions that they and advocates say violate their basic human rights.

“There’s some people that are in there that are innocent, and there’s some people that are not innocent, but we cannot give them a death sentence,” Melly Rios, the wife of Stateville inmate Benny Rios and mother of two, said. “There’s something in there that’s killing these men.”

Hess declined to answer many specific questions about inmates’ allegations, including what procedures the department took to isolate Ehlers from Scott when he first began exhibiting symptoms. In some cases she cited privacy concerns, or offered general statements regarding specific allegations.

“How do you deal with a death in the family when you feel like you gave him the virus that killed him?” Ehlers wrote of Scott. “How do you deal with it knowing that he didn’t have to die if these people had just done the bare minimum and moved him?”

As Illinois reopens, advocates and experts worry that infection rates could continue to climb in Stateville and other prisons without improved practices and continued vigilance. But Stateville is only a microcosm of what’s occurring in prisons across the country.

Nationwide, the known infection rate for COVID-19 among those in prisons and jails has been about 2.5 times greater than the general population, according to The Washington Post. The New York Times reports that at least 70,000 people across U.S. jails and prisons have been infected with COVID-19, resulting in more than 600 inmate and worker deaths. With nearly 2.3 million people held in the U.S. criminal justice system, prison overcrowding, a lack of PPE and proper sanitation has made these facilities epicenters of the pandemic.

“The virus bloomed like a malevolent flower, spreading everywhere,” wrote Ehlers. “Still nobody paid any attention, nobody cared.”

Silence inside

Since the pandemic started, the usual sound of men whistling and hollering across the cell house has been replaced by a quietness that inmate Benny Rios says he’s never experienced before at Stateville, where he’s been since 2003 serving a 45-year sentence for a murder conviction. Men curl up in their beds, aching from chills and fevers, he said, while others attempt to wash their cell walls using dirty rags and hotel-sized bars of soap that some will later use to wash their bodies.

Rios, 42, said that when he watched news reports about the virus in early March, COVID-19 seemed like a distant threat. That changed when Dr. John Walsh, the medical director at Saint Joseph’s Medical Center, announced on March 30 that 100 Stateville inmates might die if proper protocols weren’t enacted.

“That hit me like a ton of bricks,” Rios said. Suddenly, COVID-19 was at the prison’s front gates and it was no longer a matter of if the virus would infect the men inside Stateville but when. Some said they believed the virus was already in Stateville even before the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were announced among two staff members and one inmate at the prison on March 25.

Raul Dorado, 41, said when he first saw fellow prisoners exhibiting symptoms, the prison was not yet on lockdown. “I noticed that many more than usual were sick,” wrote Dorado, who has been at Stateville since 2000, serving a life sentence for a murder conviction. “Some said things like, ‘I don’t know what the hell this is, but it’s kicking my ass!’”

In the days before Walsh’s announcement, Dorado said he watched as Joseph Wilson, one of his close friends at Stateville, clutched a nearby railing, attempting to walk to his cell after visiting the healthcare unit.

Wilson, often called “Big Fella” by other prisoners, was soon hospitalized at St. Joseph’s Medical Center. On April 13, Wilson, along with another Stateville prisoner, Thomas McGee, died from COVID-19, as indicated by documents obtained from IDOC.

After hearing about Wilson’s condition at the hospital, Dorado grew worried about his own COVID-like symptoms, especially given his underlying heart condition. Dorado was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation in 2018, a type of heart arrhythmia that increases the risk of blood clots and stroke.

“I feel fragile, like a porcelain plate slipping out of a child’s hand,” wrote Dorado about his mental state. “Disposable, like a bent spork.”

Several studies have shown that prisoners have a higher rate of medical conditions than the general population, including asthma, cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes, hepatitis C, HIV and other immunodeficiencies. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, such conditions can make people more vulnerable to complications if they contract the virus.

According to Hess, individuals in custody who have underlying health conditions are being reviewed for medical furloughs, meaning they could temporarily leave prison while the governor’s emergency declaration related to the pandemic is in effect. In the meantime, she said that all inmates continue to be monitored daily for their symptoms, are given masks, and receive “ongoing education on the importance of wearing a mask, proper hand-washing, and deep cleaning.”

A lack of cleaning supplies and PPE

Since the lockdown, instead of going to a dining area men inside Stateville wait in their cells as correctional officers and fellow prisoners known as the “cell house help” deliver their daily meals: trays of deli meat, stale bread or ramen noodles, inmates and their family members note. Prisoners hold out their hands for correctional officers to spray one of the likely few squirts of hand sanitizer they’ll receive all day, Ehlers said.

Hess did not specify how much hand sanitizer inmates receive per day, but said all staff and incarcerated individuals are provided with hand sanitizer, antibacterial soap and cleaning supplies.

But multiple inmates and their family members have repeatedly said that some of the men inside have resorted to cleaning their cells with dirty rags and either their personal bars of soap or watered down bleach provided by Stateville staff.

“One morning while I was on my hands and knees cleaning my floor, I was overwhelmed with emotion, feeling my tears wanting to flow out of my eyes,” Rios said. “I began to pray as I cleaned.”

According to Hess, each individual in custody receives a new KN95 mask each week, but some inmates said they’ve received only a handful of single-use face masks over several weeks, and no gloves.

In an April 21 letter, Dorado said that since Stateville went on lockdown on March 14, he had received a total of three single-use face masks.

Several programs that provide higher education in Illinois prisons have started fundraisers and donation drives to help those inside the prison get supplies to protect them against infection.

Since mid-March, the Northwestern Prison Education Program, which offers college-credit courses to incarcerated men at Stateville, has raised over $31,000 which it used to purchase and donate supplies to Stateville, Logan Correctional Center, Cook County Jail and the Juvenile Detention Center in St. Charles. The group purchased over 12,000 bars of soap, nearly 5,000 surgical face masks, 10,000 nitrile gloves, 1,000 isolation gowns, over 550 gallons of hand sanitizer and 1,000 individual hand sanitizer pumps, according to its website.

The Illinois Coalition for Higher Education in Prison, an alliance of programs and educators, has also donated over $50,000 worth of soap and hand sanitizer to prisons and jails across Illinois, according to a June 17 press release.

“People held in Illinois prisons and jails and family members have reported a shortfall of soap, hand sanitizer, and PPE in these facilities as well as an inability to socially distance because of overcrowded conditions and a lack of regard for social distancing guidelines,” said a press release from the ICHEP.

But despite these donations, Ehlers, who is also a student in NPEP, wrote in his letters that much of those supplies have not made it to inmates, a statement echoed by other inmates. According to Dorado’s late-April letter, inmates “were left to fend for ourselves while staff were provided with face masks, full PPE [and] hand sanitizer.”

Without regular access to hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes or the like, inmates feel they are at constant risk of contamination. Melly Rios said her husband worries that his belongings could be contaminated during regular shakedowns, when correctional officers search cells and the men in them for contraband, sometimes requiring the men to strip their clothes off.

“They come into our cell, touch your cup, your bowl, your bedding and your pillow, all with filthy gloves that have been worn for hours,” Ehlers wrote. “These shakedowns feel like harassment.”

IDOC did not respond to questions regarding prison shakedowns.

Amid the alleged shakedowns and the lack of cleaning supplies and PPE, the men inside Stateville say they also fear they could be exposed to the virus by making calls to loved ones. During the pandemic, several inmates explained they make calls using an old-fashioned landline phone that is attached to a long cord and passed cell to cell without being sanitized. The men are responsible for disinfecting the phone themselves, inmates said, but with little to no cleaning supplies, properly sanitizing the phone is impossible.

“[The phone] is the filthiest thing in here,” Ehlers said. “Guys breathe into it, cough on it, everyone touches it, and we are not given anything to clean the phones or our hands with after touching it.”

Commissary access reduced

Before Stateville went on lockdown, prisoners were able to go to the prison commissary to buy items like bottled water, toothpaste, soap, Little Debbie cakes and other snacks at the commissary. But since lockdown, their purchases are made using paper request slips that IDOC says they can submit once a month. According to a May 28 statement from Hess, inmates had a $100 monthly spending limit because supplies sold in the commissary have been harder for IDOC to restock during the pandemic.

In a June 3 message, Ehlers wrote that the monthly spending limit had been raised to $125 but “it doesn’t fix the problems,” because there is still a cap on how many items the men can buy. According to Ehlers, inmates are only allowed to purchase up to four bars of soap through the monthly commissary slips, costing between 75 cents to $2 each. He also said that Stateville staff give inmates two free hotel-size bars of soap per week, but the tiny bars don’t last long when being used to wash clothes, bodies and cells.

In response to questions about commissary access, Hess reiterated that, “hand sanitizer, antibacterial soap, and cleaning supplies are being made available to all staff and incarcerated individuals.” She did not provide further comment.

‘Tent city’ and F-House erected as COVID-19 spreads

In interviews and letters, inmates said that when men complain to prison staff of COVID-19-like symptoms, some are tested and some are sent back to their cells without tests, where they might infect their cellmates or “cellies.”

Taurean Decatur, who has been in Stateville since 2013, according to IDOC’s website, said that when his cellie developed a fever over 100 degrees along with other symptoms in mid-March, he feared contracting the virus was “inevitable,” as they both remained in a cell together.

| RELATED:

|

Decatur, 29, said he and his cellmate were tested on March 29, and April 1, respectively, and were later told they were infected with COVID-19. Shortly after being tested, Decatur said he was moved to the prison’s healthcare unit on April 2 but wasn’t seen by a doctor until April 9.

“I was placed in a room with another positive individual where we resided for eight to nine days with dysfunctional plumbing,” said Decatur, who added that his symptoms included headaches, respiratory issues, loss of smell and taste, bone and muscle aches and cold sweats. “I was told to lay down and drink water for all other symptoms, which made no sense considering the sink was broken.”

IDOC could not confirm Decatur’s statement, citing that inmates’ medical information is confidential. The department also did not provide a comment regarding the “dysfunctional plumbing” and other housing conditions Decatur said he faced while in the healthcare unit, or the type of medical treatment he received. IDOC spokesperson Greg Runyan said, “Policy is that any offender referred to a medical doctor is to be seen within 72 hours.”

According to Decatur, after his time in the prison’s healthcare unit, he was moved to “tent city,” an area located in the facility’s gymnasium where inmates who have tested positive for COVID-19 or are experiencing respiratory symptoms are housed in what Hess described as “heavy duty Alaskan tents.” On April 14, the medical director cleared Decatur to return back to his original cell, said Decatur, who is serving a 65-year sentence for a murder conviction.

Along with “tent city,” some inmates who test positive for COVID-19 or are awaiting test results have also been housed in F-House, or the “roundhouse,” which was reopened on May 5 after being shut down in 2016. It was the last such roundhouse open in the U.S. at the time it closed, according to IDOC, and the “antiquated” panopticon layout presented “safety and operational hazards.”

As of May 21, Hess said 85 men were being housed in F-House, including those testing positive, waiting for results, and inmates with jobs in the prison. “Each group is sufficiently distanced from the other,” she said, adding that F-House was inspected by the Illinois Department of Public Health and repaired before reopening. But inmates say the poor conditions that F-House was once notorious for, still persist today.

According to a 2011 report from the John Howard Association, an independent organization that monitors prisons, F-House was plagued with “substandard” ventilation systems, cockroach infestation, poor sanitation and “malfunctioning” plumbing. Similar claims were made in a 2016 lawsuit, Lyons v. Vergara, regarding conditions in F-House.

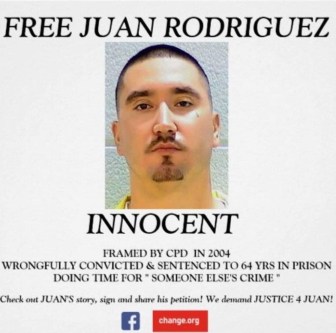

Juan Rodriguez was one of the men moved to F-House in early May. According to Rodriguez, on May 7, he was tested for COVID-19 twice. The first was a “rapid test,” Rodriguez said, and healthcare staff told him he was negative after about 15 minutes. Rodriguez, 33, said he was tested again and on May 8, security staff told him that the test came back positive and he was moved to F-House for a 14-day quarantine.

Rodriguez told his wife that other inmates were also moved to F-House after testing positive for the virus, then later told that their results were actually negative. This caused many to worry they could have contracted the virus while housed with infected inmates in F-House. IDOC spokesperson Runyan said that “while awaiting their test results, offenders are placed in isolation. They are not placed with anyone who is not symptomatic.”

Rodriguez, who has been at Stateville since 2007 on a 50-year sentence for a murder conviction, said he demanded to see a written copy of his test results because he was skeptical of the differing outcomes, but has not received one. According to Hess, all test results are communicated verbally.

Only the beginning

Inmates and prisoners’ rights groups fear that without drastic action, the current situation at Stateville will only escalate and infections will increase in other Illinois prisons too.

“Once [the virus] is introduced into a prison … it will spread like wildfire,” said Alan Mills, the executive director at Uptown People’s Law Center, a legal clinic which filed three cases — including a federal class action lawsuit on April 2 — demanding the release of Illinois prisoners considered most vulnerable to COVID-19.

“No one in Illinois has been given the death penalty, but if proper actions aren’t taken, for many this will be a death sentence,” Mills stated in a May 21 press release.

With nearly 37,000 prisoners held across 24 state prison facilities in Illinois, according to a March 2020 IDOC prison population data set, the contagion in prisons could also fuel infections in surrounding communities, home to thousands of IDOC staff members.

| RELATED:

|

“If coronavirus should spread through the [downstate] Illinois prisons, we’ll have a real public health disaster,” Mills said, adding that there are simply not enough ICU beds in rural Illinois hospitals to support a large number of infected prisoners. For example, in Randolph County, home to Menard Correctional Center which holds 1,758 inmates, the only hospital that has ICU beds is Chester Memorial, with a total of two, according to data compiled by the Illinois Department of Public Health. According to the IDOC, there are no reported cases of COVID-19 among inmates at Menard.

To minimize the risk, civil rights organizations have been calling on IDOC to reduce the prison population. The Cook County Jail reduced its population by about 1,500 before the effort was stalled due to a lack of electronic monitoring equipment for home confinement. Other states like North Dakota, Wisconsin and Virginia have taken measures to reduce their prison populations during the pandemic.

On March 26, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker issued an executive order temporarily suspending all new prison admissions from county jails. Pritzker also signed an executive order in early April that expanded inmates’ eligibility for medical furloughs during the pandemic. The order gives IDOC permission to “allow medically vulnerable inmates to temporarily leave IDOC facilities, when necessary and appropriate.” As of June 1, 109 individuals have received furloughs following Pritzker’s executive order, according to an analysis of state data by the criminal justice reform organization Restore Justice.

But advocates and family members of incarcerated loved ones have been calling on the governor to issue wider reforms. Mills points to an existing Illinois law that he says could allow around 9,000 state prisoners with lower-class felonies to serve the last 90 days of their sentence under home confinement. According to Mills, IDOC has been slow in its efforts to release legally eligible inmates in part because there are not enough personnel to review each case.

“Unfortunately, Illinois is not a computerized state, so all that information is contained in paper files,” Mills said. “[It] requires somebody physically opening up the files and going through page by page to figure out what’s going on.”

“We are the forgotten”

With the pandemic expected to continue for many months at least, Stateville inmates and their family members and advocates worry that there will be more sickness and death unless IDOC takes significant measures to improve sanitation, testing and isolation measures, and overall health care. The risk could increase as the state reopens, or if a feared second wave of the virus materializes, since correctional officers could be exposed in their communities and bring the virus into the prison.

Meanwhile though COVID-19 has shed more light on the dire sanitary and health conditions inside Stateville, inmates and their supporters say it is only the latest example of the way people are stripped of their basic human rights and dignity once they are incarcerated.

“This place has always been miserable,” wrote Ehlers. “It just sucks the soul, the humanity right out of you. I don’t even feel human anymore.”

As Illinois officials focus on safely reopening the state and addressing the economic damage wrought by the pandemic, prisoners and their advocates worry that prison reform will fall by the wayside. They are pleading with the public and demanding officials to pay greater attention to the poor conditions and unnecessary suffering in prisons that have been highlighted by COVID-19, and to keep pushing for reform even after the pandemic ends.

“We’ve always known we are the forgotten, the last in line,” Ehlers wrote. “We’re sick and we’re dying and no one cares. Do you?”

Josh McGhee and David Eads contributed analysis to this piece.

Correction: An earlier version of this post erroneously attributed a quote from an Illinois Coalition for Higher Education in Prison press release.