Another Life, Episode 1.

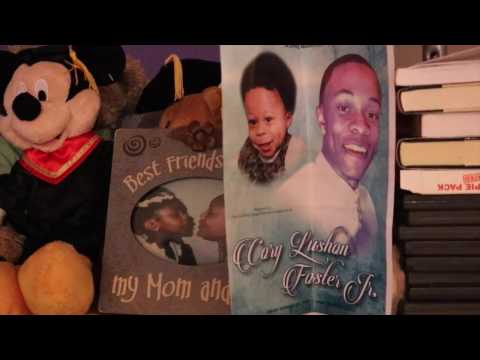

While Chicago’s gun violence epidemic continually makes local and national headlines, the voices of those most directly affected often go unheard. A new documentary series that debuted earlier this year seeks to redress that. “Another Life” portrays three young Chicagoans coping with the aftermath of their loved ones being gunned down. Amanie Foster lost her cousin to a shooting last December. Martinez Sutton continues to cope with the 2012 police shooting that took the life of his sister, Rekia Boyd. And Perrick “Moon” Robinson, a high school teacher and basketball coach, deals with the shooting death of a friend and standout player.

The series takes the uncommon approach of intimately following its subjects for months as they navigate trauma and mental health struggles, and seek to honor the memories of those they lost. It also features original poetry by Shannon Smith.

Documentary filmmaker Morgan Elise Johnson and journalist Tiffany Walden, both Chicago- area natives, produced the series. They moved back to the city last year to create a new online platform, The Triibe, for black millennials in Chicago. We spoke to Johnson about what The Triibe hopes to accomplish with the series.

What inspired you to create the “Another Life” series?

In January, I don’t know what it was, I think probably it was Donald Trump as president. I heard so many negative things about Chicago in the news and out of the mouth of the president-elect, specifically referencing Chicago as like the face of everything wrong with the black community. And it felt very urgent for me to produce a counter-narrative to that. If we’re going to focus on reshaping the narrative, we need to tackle gun violence because that is a hot-button topic across all newspapers. And we need to do it in a way that is completely different than what everybody else does, which is show up on the worst day of someone’s life and ask them to tell a story. We need to talk about gun violence from the point of view of dealing with trauma and trying to convey this message of healing our community, which we don’t talk about enough.

What do you feel about news coverage of Chicago’s gun violence epidemic?

I barely even watch the news, to be honest, because I know what I’m going to get. I’m going to get the body count. And I’ve really just started to wonder what purpose that serves. Like, what does it do? And one of the devastating things about being black in Chicago or from Chicago is that wherever you go right now, you could be anywhere and you tell people, ‘I’m from Chicago,’ and they will say, ‘How do you survive? Oh my God. How did you make it out? Oh my gosh, is it really that dangerous?’ That is our identity. That’s devastating as a black person to think that everyone associates you with violence and it’s because of the way the media has propelled this narrative, as if it’s the only thing that matters. Yes it’s important to talk about gun violence, but maybe we can do it in a way that’s a little bit more impactful, in a way that makes a difference. If we know that the numbers are not shrinking, then maybe the way we tell the story needs to change.

Personally, a part of ‘Another Life’ is just doing this for me because when I moved to D.C. for a couple months and I told people I was from the Chicago area and they said those things to me I’m like, ‘Really?’ Black culture is so much richer than this. And we need media to reflect that.

Can you tell me about why you decided to incorporate poetry in the docu-series?

I wanted there to be some kind of like community aspect to the making of ‘Another Life’, meaning I wanted the people of Chicago to be a part of actually producing this series.

So I sent out questionnaires to people who I filmed. Did you notice over the poetry sometimes there are portraits of people? Especially in episode one, the whole opening sequence that introduces ‘Another Life’ is a portrait of three men on a porch. My initial goal is to film a bunch of portraits of black millennials throughout Chicago who have experienced gun violence, and while filming their portrait, I asked them questions about their trauma. And so the poem is kind of like a community statement based on the words that other people have described, how they feel about their own trauma and how they can heal.

So even though I’m only following a couple of characters, I want it to be a more expansive exhibit that highlights the numerous cousins and siblings and friends who have lost someone. Because it’s really our generation who’s suffering. And a lot of times the media, they cover the crying mother, the crying father but somebody just lost their best friend and that person they spend time with every day. So that’s what the portraits are about. And the poetry is inspired by the people we interview.

Like for episode two the opening poem is definitely inspired by Moon and by him feeling there’s a misconception about black men standing on corners. We drive past them and we assume that they’re dealers but Perrick said to me, ‘You know, I’m a grown man. I’m 31 years old and I stand on the corner because that’s our culture, that’s how we grew up. We stand on corners and that’s how we meet up with our friends and we don’t have a community center to go to on our corner, so we hang out on the block.’

In addition to portraying the subjects’ mental health struggles, the series also shows them coping through different outlets such as music, activism or mentoring, as in the case of Perrick “Moon” Robinson, the basketball coach.

I really wanted to have a character that brings some hope to the story and also could be my character that represents a call to action for millennials. Actually, all of our characters despite their trauma are doing something. So that’s the thing with ‘Another Life,’ I want to definitely dispel this idea that the black community only cares when a police shooting happens. The black community, even though we are traumatized, is going above and beyond to push through the PTSD. Amanie, while she’s grieving, is starting a foundation. You know what I mean? I wanted another character like Moon who more explicitly can show how he’s mentoring black youth and how mentoring is helping him heal from his own trauma.

Tell me more about the decision to profile both people who have been impacted by neighborhood violence and also police violence. Was that intentional?

That was definitely intentional because I felt like a lot of times people like to separate the two. I mean there are different things happening. On one level, there is state-sanctioned violence. So tax dollars are being used to actually terrorize and kill black people. And then, on the other hand, there’s so-called black-on-black violence … people kill who they know, it’s not necessarily because they’re black.

And many times people say, ‘Why isn’t the black community doing something?’ And my answer to that is that, one, they are doing something. Two, maybe, just maybe they’re grieving. Three, maybe they’re traumatized. Four, maybe they don’t have the resources to do something because like what is a group of poor people, like what can they actually get accomplished when our government has thousands and thousands of dollars to pour into whatever they want to pour into, a development of a stadium or whatever, you know?

I want to show that no matter if it’s a police shooting or if it’s the so-called black-on-black crime, everybody’s hurting. … I feel like a lot is focused on the outrage that happens right after somebody is killed and not much is focused on healing and rebuilding and maybe some of these revenge shootings would stop happening if people got counseling and mental health facilities.

Episode 2:

Episode 3:

Episode 4:

From reading this article, the author fails to mention one of the foundational issues that directly relates to the levels of violence seen today in many (not all) black communities whether in South LA, Baltimore, NY, or Chicago. That single issue – most important of all issues, in my opinion – is the breakdown of the black family structure and the high level of single-parent families. If I were the author, I would certainly included that issue in an effort to bring a more balanced presentation to the public view. As it stands, the blame is nearly completely piled on government and the outside world. Personal responsibility must play a role if the black community is to achieve its true potential – which is considerable. Heal the families and you will heal much of the violence.