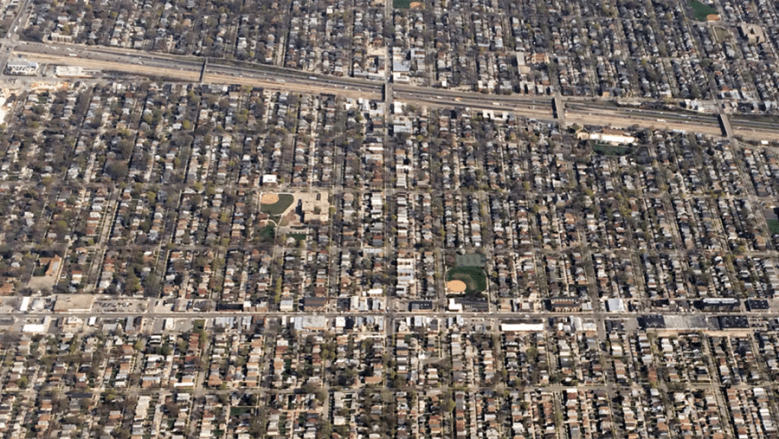

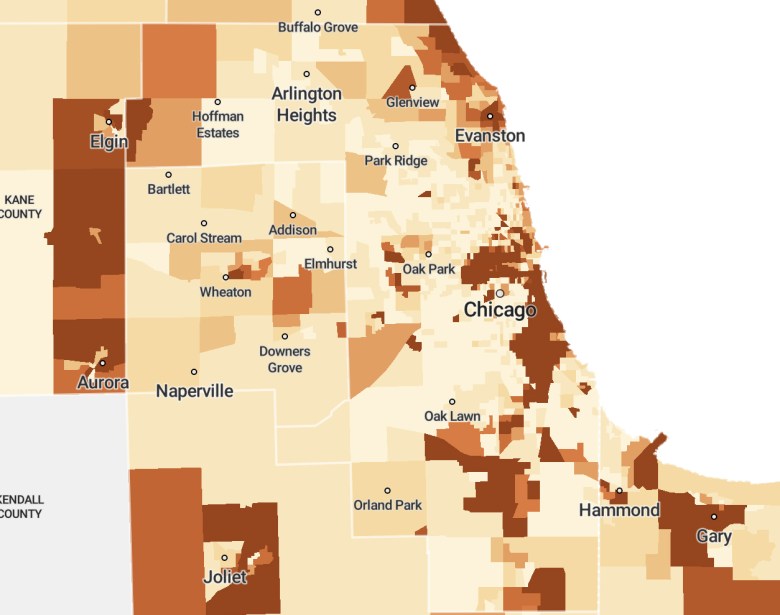

The first article in this series on financial disparities in Cook County, “Wealth Inequality and the Racial Wealth Gap,” discussed the extent of contemporary racial inequities in the County. Black and Latinx Cook County residents are more likely to be financially vulnerable than Black and Latinx individuals elsewhere in the country, and significantly less likely to be financially healthy than white residents of Cook County, even if those white residents are in the same income bracket. Far fewer Black residents own their homes than white residents, regardless of income. And Cook County remains deeply segregated.

That last fact is key, because in the United States, where you live determines your school choices, your social services, your job opportunities, and your safety. It determines how heavily you’re policed, how easy it is to access fresh food, and how much government investment your community receives. It determines whether you breathe clean air and have access to clean water. It even determines the average temperature: Black neighborhoods, segregated and ignored politically in the 20th century, are now much hotter than white neighborhoods.

Therefore, this article focuses on Chicago’s history of segregation. From first settlement to racial covenants to suburbanization, the story of our city is one of structural racism and its lingering effect: unequal geography.

INDIGENOUS CHICAGO

For more than a century before Chicago was “discovered” by French missionary Father Jacques Marquette in 1673, the area that is now Cook County was the seasonal buffalo hunting, fishing, and trading grounds of many Indigenous Tribes. These Tribes included the Potawatomi, the Menominee, the Miami, the Ojibwe, and the state’s namesake, the Illinois. Members of the Miami Tribe showed Marquette the geographic value of Chicago as a portage site between the Des Plaines and Chicago Rivers. Many contemporary city streets, like Lincoln Avenue and Vincennes Avenue, follow the paths of tribal trails.

Where there are now paved roads, three hundred years ago there was swampland filled with wild onions and leeks. “Chicago” comes from the Algonquian word for these leeks: “Checagou.” In the 1770s, the first permanent non-Indigenous settler came to Chicago—Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. The Black fur trader’s wife was a Potawatomi or Illinois woman named Kittahawa.

Seeking to avoid the English and later the Americans, some Indigenous tribes moved west out of the Great Lakes region as early as the 1760s, Indigenous historian Susan Sleeper-Smith told The Chicago Reporter.

But the region’s Indigenous population was decimated in the 1810s and 1820s. Warfare and disease killed many. Others were forced to abandon their land due to a series of treaties between Tribes and the United States government. The U.S. would later violate or fail to uphold the terms of many of those treaties.

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized Jackson to forcibly relocate remaining Tribes west across the Mississippi, freeing up space for white settlement. At the time, newspapers like the Philadelphia Enquirer spoke of the cost “per head” of “removing” “Indians” westward.

Those who remained were forced to go underground: some simply remained nomadic, others lived in the wetlands on the fringes of the young city, trading furs to Chicagoans until the fur trade died out in the 1890s. Still others converted to Christianity and adopted American customs.

By 1870, only six reported “Indians” lived in Cook County. Dr. Sleeper-Smith believes this was a massive undercount. “If somebody knocks at your door and says ‘I’m the census taker,’ half of your family is exiting through the rear windows.”

Six may be an undercount, but it is undisputed that the city was home to relatively few Indigenous people. Until the 1950s, that is, when Chicago’s population swelled during “Relocation”—the voluntary but highly encouraged movement of Indigenous people from reservations to cities. The policy was aimed at assimilation, but also in part at improving the livelihoods of Indians, who—on underfunded reservations—suffered terrible poverty and had a life expectancy of just 45 years.

Relocation, however, was overpromoted and underfunded. Philleo Nash, Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the 1960s, remarked that Relocation was “essentially a one-way ticket from rural to urban poverty.”

The legacy of indigenous Chicago, Sleeper-Smith said, is a legacy of marginalization. And that legacy is just the first chapter in Chicago’s 200 year long history of discrimination, segregation, and disinvestment, which has left present-day non-white and white Chicagoans in vastly different circumstances, especially with regards to housing.

CHICAGO’S GROWTH

Chicago has forever been a city of growth and change. “It is hopeless for the occasional visitor to try to keep up with Chicago,” the author Mark Twain remarked in 1883. “She outgrows his prophecies faster than he can make them.”

Between the industrial East Coast and the expansive western territories, Chicago was perfectly placed as a hub for America’s westward expansion; from the 1830s to the 1880s, settler colonialism brought Chicago from a tiny trading and railroad post to one of the United States’ largest cities. Chicago historian Ann Keating told The Chicago Reporter that, in essence, government land was quickly converted into private real estate.

Chicago was chartered in 1837, and Cook County did not show up in the U.S. Census data until 1840. Even then, the county had a population of only around 10,000 people. 20 years later, the county was home to almost 150,000 residents. Even the Great Fire of 1871 and the national depression of 1873 could not slow the County’s rapid growth. By 1890, Chicago alone was home to more than a million people, making it the second largest city in the nation, behind only New York City.

As the city grew, it also diversified, albeit slowly. In 1840, with Native Americans forced out of the region, only 55 residents of Cook County identified as “non-white.” By 1860, the Census was asking Americans whether they were “white,” “colored,” “Indian,” or “Asian.” More than 99 percent of Cook County residents identified as white. Many of these white residents were European peasants pushed out of Great Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia by industrialization.

Since the Indian Removal Act, Blacks have consistently been the city’s largest minority, but even by 1900, fewer than 50,000 Chicagoans identified as Black.

EARLY BLACK CHICAGO

Before Illinois was admitted to the Union as a free state in 1818, traders in the Chicago region enslaved Black and Indigenous people. Even into the 1830s, free Black Illinoisians were denied many of the basic freedoms guaranteed to their white counterparts. In southern Illinois, many free Blacks served as indentured servants in salt mines, a practice not banned until 1917. And, as WTTW reported, Illinois Black Codes in place through the end of the Civil War prohibited Blacks from voting, owning weapons or real estate, and gathering in groups of three or more, among other prohibitions.

Just after the Civil War, the infamous Great Fire of 1871 received significantly more media attention than another fire on July 14th, 1874. The Great Fire killed more than 300 people and displaced more than 100,000. The “forgotten” fire killed 20 people, and where the Great Fire had upturned all of Chicago, the forgotten fire was unequal in its displacement.

The victims of this second fire were mostly Blacks and Jews living just south of the Loop. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that the fire “swept the district in which the larger portion of the colored population of the city was located.” Many of the buildings burned to the ground were wooden tenements that had been moved downtown just years earlier. “These buildings were packed so closely that a dozen were often placed upon a single lot.”

The fire struck “those who, though they lose a little, lose everything,” The Daily Tribune reported.

Almost the entire Black population of the city, small as it was, moved south after the fire, establishing the roots of the Black Belt on Chicago’s South Side.

THE ROOTS OF MIGRATION TO CHICAGO

Soon, the city would swell further, as the Great Migration brought 500,000 Black Americans to Chicago. Seeking to escape segregation and racial violence in the Jim Crow South and eager for better economic opportunities, 1.6 million southern Blacks moved north and west starting in the 1910s. Chicago was one of the most popular destinations.

Northern migration was not a new phenomenon—by 1804, all Northern states had abolished slavery, and scattered free Southern Blacks moved north. Of course, most Southern Blacks could not escape because they were trapped by the system of chattel slavery. After the Civil War and the Constitutional ban on slavery, most Black Southerners stayed in the South, expressing genuine belief in the promise of Reconstruction.

By 1877, Reconstruction had ground to a halt, but there was still little reason to leave the South—Northern cities were frequently inhospitable to Southern Blacks, and Northern industrial sectors employed mostly European immigrants. The northward and westward migration that did occur was largely from rural communities to other rural communities.

The 1890s, however, brought the specter of Jim Crow to the South. In the next 20 years, every state below the Mason-Dixon line would pass Jim Crow laws, completely separating Blacks and whites. Trains, streetcars, water fountains, public utilities—all were divided white/Black; whites were given better accommodations, Blacks worse or none.

Lynchings rose in frequency. From 1882 to 1968, the NAACP reports, 4,743 Americans were lynched. Most of these victims were Black, and most of the lynchings took place in the South, especially in Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas. On average, more than one lynching occurred each week.

Then came World War One. From when the United States joined the war in April of 1917 until the war’s end a year and a half later, five million working Americans would leave the U.S. to fight. Legislation like the Immigration Act of 1917 and the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 banned most Asian immigrants and instituted strict quotas on European immigration to the United States.

So, with the war effort demanding expanded infrastructure, Americans shipped overseas to fight, and foreigners prohibited from entering the country, there was suddenly an excess of northern manufacturing jobs.

Until the 1920s, most Black Chicagoans had been employed in domestic positions. Now, for the first time in the nation’s history, Southern Blacks could find real opportunities in the heavy industries of the North.

THE FIRST GREAT MIGRATION TO CHICAGO

The nation’s leading Black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, published glowing portrayals of Chicago’s promise, often comparing the city to southern cities where there were fewer opportunities for Black laborers. The Defender also published guides for arriving Blacks—lists of social organizations and advice like “don’t allow yourself to be drawn into street brawls.” From 1915 to 1930, more than 50,000 Black migrants arrived in Chicago with high expectations of improved education and employment. But Chicago, though not quite the Jim Crow South, was still segregated.

As James Grossman wrote in Land of Hope, arriving Blacks “were limited to the slowly expanding ‘Black Belt’ on the city’s South Side, a smaller ghetto on the West Side, and scattered enclaves elsewhere in the city.” This pattern of racial segregation lasted through the 20th century and continues to define the city’s geography.

In 1919, with 115,000 Blacks now living amid 3 million whites in Chicago, racial animosity toward the newcomers hit a boiling point.

On July 27th, Black teenager Eugene Williams floated on a raft across an imaginary line separating the white and Black waters of Lake Michigan. White beachgoers threw stones at Williams until he drowned. When police refused to make arrests, rioting erupted. In response, white mobs marauded through the city, attacking Black Chicagoans, who fought back.

Hospitals in the city’s Black Belt were “filled with the maimed and dying,” The Chicago Defender reported, alongside pages of depictions of mob violence considerably too graphic to restate here.

Black businesses in white neighborhoods were looted and burned, as were white businesses in Black neighborhoods. White undertakers refused to accept the bodies of Black victims for fear of retributive violence.

The majority of the violence occurred on the South Side. Riot arson was common, concentrated especially in Fuller Park.

When the Illinois National Guard finally brought the “quake of racial antagonism” to an end on August 3rd, 38 Chicagoans lay dead, hundreds had been injured, and more than a thousand Black families had been left homeless.

Chicago was one of many (mostly Northern) cities where riots erupted during the Red Summer of 1919. These riots were in large part a white response to the country’s changing demographics, as Blacks moved north and soldiers returned home from World War One.

BLACK SETTLEMENT IN CHICAGO

By 1920, Cook County was home to more than 3 million people. Even with the Great Migration underway, only 4 percent of those residents were Black. Most Black Chicagoans lived on the South Side, generally as far north as South Loop and as far south as Washington Park. This so-called “Black Belt” extended to what is now the Dan Ryan Expressway in the west and to Cottage Grove in the east.

Many parts of the city now home to large Black populations, like Englewood, Hyde Park, and Roseland, were home to few Black Chicagoans. The city’s Hispanic population was so small it was not even recorded by the 1920 Census.

Like many diaspora communities, early Black Chicagoans settled close to one another. As the Great Migration brought more Blacks to the city, these newcomers found housing and employment where earlier generations of Black Chicagoans already lived. This was in part a choice—to live with one’s community—and in part forced due to ambient racism.

In the 1920s, as more Blacks arrived in Chicago than ever before, alongside Russian Jews, Germans, Italians, Poles, and Swedes, Chicago became one of the first cities in the country to take proactive legal steps to stem the tides of demographic change.

CHICAGO’S RACIAL COVENANTS

Though the Supreme Court’s 1917 ruling in Buchanan v. Warley declared residential segregation laws unconstitutional, it said nothing of segregation in private housing developments. So, in the 1920s, racially restrictive housing covenants proliferated in Chicago.

These racial covenants were clauses inserted in property deeds—for both new and existing homes—that forbade any occupancy by “negroes,” or limited occupancy to members of the “Caucasian race.” Ninety-nine percent of Chicago’s covenants targeted Blacks.

Racially restrictive covenants were not new in the 1920s, but they were newly weaponized. The National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) took the lead, and real estate developers proudly advertised their racial covenants in newspapers like The Chicago Tribune. “Every lot is highly restricted,” one ad read, “protecting the property from the encroachment of every undesirable element.”

Often, white homeowners were active participants in this effective segregation. Covenants created for unsold lots, called “plat restrictions,” were written by developers. But in existing neighborhoods, “agreement covenants” were written by groups of neighbors.

Such practices were not only expanded in the twenties, but also formalized. NAREB, in their 1924 code of ethics, declared that a realtor should never introduce into a neighborhood “members of any race or nationality… whose presence will clearly be detrimental.”

At one point in the 1920s, more than 80% of Chicago properties were restricted by racial covenants. And, in 1926, in Corrigan v. Buckley, the Supreme Court decided it had no power to prevent the adoption of these covenants, because they were private agreements.

Accompanying this explicit racism was quieter exclusion. Neighborhoods adopted development restrictions based on home size and land use that essentially excluded poorer Chicagoans—many of them Black. This was more than mere separation of neighborhoods by wealth. This was a guarantee that wealthier neighborhoods would remain wealthier, in perpetuity.

CHICAGO DURING THE DEPRESSION

By the late 1920s, the population of Cook County had grown to almost four million people. But as Chicago expanded in all directions, Black Chicagoans remained confined to the Black Belt. Richer Blacks lived further south in the Belt, poorer Blacks in older housing farther north.

Then, in the fall of 1929, the stock market crashed. Over the next two years, banking collapsed, unemployment soared, and severe deflation hit most sectors of the American economy.

Chicago was among the country’s hardest hit cities, due to its reliance on heavy industry. By 1933, the city’s manufacturing sector had been halved; many Chicagoans were without employment, food, or housing, and there was widespread public unrest. Blacks were hit hardest: 40 to 50 percent of Black Chicagoans lost their jobs during the Great Depression.

Banks, desperately in need of capital, demanded mortgage payments. Many homeowners, now unemployed and unable to pay, lost their houses to foreclosure.

President Franklin Roosevelt, seeking to stabilize the real estate industry and boost homeownership, created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) in 1933 and 1934, respectively. HOLC was a temporary agency designed to refinance home mortgages—in other words, to erase existing, difficult-to-pay mortgages and replace them with mortgages better suited to both homeowners and lenders. HOLC was also tasked with standardizing home appraisal processes.

The FHA’s task was to regulate interest rates and mortgage terms, and by guaranteeing that the FHA would pay back loans if homeowners defaulted, the Authority gave banks the necessary security to expand mortgage loaning.

Such roles, though highly beneficial to the real estate sector and the national economy, would soon be weaponized to further segregate Chicago and the nation.

REDLINING CHICAGO

Chicago was the center of the real estate industry in America. University of Chicago and Northwestern University economists and sociologists like Richard Ely were on the forefront of developments in urban planning. NAREB was headquartered in Chicago, and the real estate strategies pioneered in the city were rolled out nationwide.

In Chicago, HOLC sought to standardize home appraisals, which until the 1930s had been based largely on personal judgment. To do so meant considering land value, which relied on what urban historian LaDale Winling called “the character of a neighborhood and of the neighbors.” HOLC emphasized neighborhood stability as their desired outcome and followed the then-prevailing white theory that said mixing races harmed home value and neighborhood quality.

Given that theory, the conclusion was straight forward, said Dr. Winling. “You cannot allow African Americans to move into white neighborhoods.”

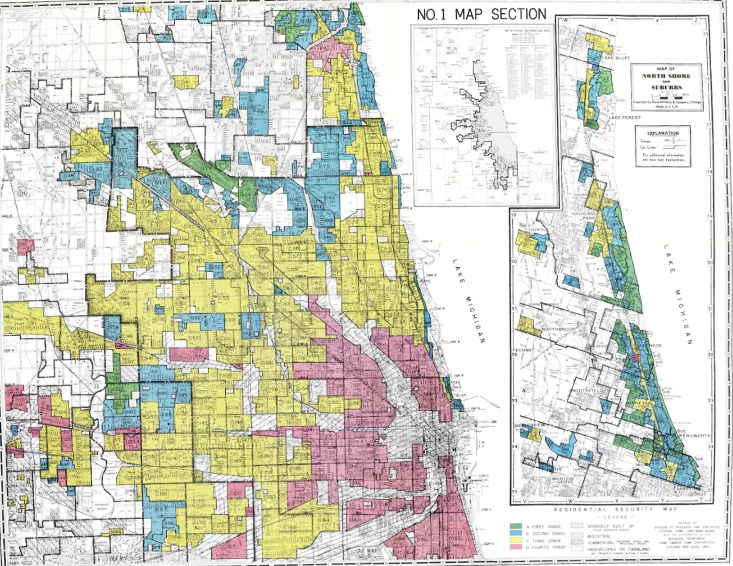

HOLC and the FHA mapped and divided almost every American city into various colored zones—green, blue, yellow, and red. Green meant “Best,” blue “Still Desirable,” and Yellow “Definitely Declining.” Red zones were given the title “Hazardous.” These zones were based on the descriptions of HOLC and FHA field agents, who worked in conjunction with the real estate industry. The maps’ purpose was fairly simple: to give the federal government assessments of home lending risk. The higher rated the zone, the less risky the loan, and the more likely a homebuyer would be able to borrow.

The concept of assessing loan risk is not itself radical, but the basis on which these color determinations were made was pseudoscientific at best, racist and nativist at worst.

Any neighborhood with 10 percent Black residents was declared Hazardous, or “redlined.” “This is where we see the transition from individual explicit racism into structural housing discrimination,” Winling said.

Robert Nelson and LaDale Winling were part of a team of researchers who recently collected, digitized, and analyzed HOLC’s maps. (The FHA destroyed their maps in 1969. The reason for this is disputed.) Dr. Nelson told The Chicago Reporter that for HOLC, race was always more important than wealth or income. “More than 99 percent of Black neighborhoods were redlined and it didn’t matter in almost any case whether that was a middle class or a working class Black neighborhood.”

Studies have shown that HOLC and the FHA’s determinations were unsound. Black homeowners paid off mortgages more reliably than whites, yet white neighborhoods were given much higher ratings than similarly wealthy Black neighborhoods. Appraisers were not allowed to compare Black homes to white homes. “It bakes the race of the borrower into the home’s value,” Winling explained.

The neighborhood descriptions that accompany HOLC’s maps are not full of the coded language one might expect. They are terrifyingly explicit. Phrases like “negro encroachment,” “infiltration,” and “inharmonious races” are everywhere. With the Great Migration continuing to bring Blacks to Bronzeville, the neighborhood’s HOLC description explained that “continued influx of negroes must necessarily cause an overflow into adjoining sections. Effort is being made to restrict their encroachment.”

HOLC labeled South Works the worst area in South Chicago. Washington Park was described as “completely monopolized by the colored race.” Englewood was “semi-blighted” and West Englewood was “characterized by no pride of [home] ownership.”

Black Chicagoans were not the only group who suffered this kind of discrimination. Across the country, Jews, Mexicans, Asians, Poles, Russians, Italians, and others were redlined because of race and religion. Neighborhoods near where these minorities lived were yellowlined, because mapmakers feared the spread of “deleterious races,” even as their maps effectively limited that spread. But Black Americans were the most harshly targeted, and as the decades progressed, nativism declined quicker than racism.

The practice of redlining was just as extensive in the North as in the Jim Crow South, Dr. Nelson stressed: Almost a third of Chicago was redlined.

To encourage homeownership, HOLC and the FHA had also extended the length of the average mortgage from three or five years to 15 or 30. The ostensible logic was simple: longer payment periods meant smaller payments each period, which opened up homeownership to lower income Americans. This move to longer mortgages also stabilized housing markets, preventing boom-and-bust cycles.

But Dr. Winling believes the move to longer-term mortgages had more nefarious roots. In his view, lending agencies lengthened mortgage terms to slow demographic change—to stabilize who owned a home and who did not, for the long term.

Longer-term mortgages also facilitated redlining, Dr. Nelson said. In order for a bank to lend for 15 or 30 years, it needs confidence that the loan’s collateral—the home—will hold its value for the life of the loan. By explicitly backing racial segregation, the FHA and HOLC assured white builders and lenders that the government would not require neighborhoods to integrate and thereby (in the view of the time) threaten home values.

The 1920s and 1930s, historians stress, do not tell the complete story of housing inequality in 20th century America. HOLC used their maps for only about 10 years; the Supreme Court held racial covenants unconstitutional in 1948; and the Fair Housing Act banned redlining in 1968. But the practice continued unofficially, as private lenders took up the government’s mantle, making quiet use of racial covenants and redlining well into the 1960s.

PERPETUATING SEGREGATION IN CHICAGO

In the 1940s, World War Two brought a new wave of Black southerners to Chicago. This Second Great Migration was much larger but resulted from many of the same causes as the first: the war effort, along with economic malaise and extensive racism in the South. By 1960, 850,000 Blacks lived in Cook County. For the first time, the Black Belt was slowly expanding—as far south as 103rd Street and all the way east to the lake. In the west, Black Chicago extended almost to Cicero.

As Chicago’s suburbs developed, they remained mostly white despite this influx of Southern Blacks. In many suburban communities, there remained exclusionary lending practices keeping Blacks out even into the 1960s. After the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining, many homeowners associations began using minimum lot sizes, single family home requirements, and minimum home values. These practices no longer expressly excluded Blacks, but they were no less effective in preventing poor and working class people of color from finding homes in wealthier neighborhoods.

In the 19th century, Chicago suburbs like Riverside and Lake Forest, connected to the city by proliferating railroads, had been segregated heavily by class. In the 20th century, Dr. Keating explained, the same methods of exclusion that had kept Chicago’s suburbs wealthy were turned around and used to keep Chicago’s suburbs white. By the 1970s, formerly diverse farm towns like Naperville became “incredibly homogeneous.”

Adding insult to injury, the same practices that had prevented Black Chicagoans from living in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods then, in turn, limited their ability to buy homes even in poorer, largely Black neighborhoods. Because banks deemed those neighborhoods to be “declining,” lenders refused to extend standard 30-year mortgages backed by homes in those neighborhoods.

Instead, many Blacks had to obtain “contract loans” from predatory lenders. Contract buyers were subject to large down payments and high interest rates, and they didn’t own their houses until they had paid off their loans entirely. The seller continued to hold the deed and could evict the buyer—who had no legal protections—at any time. In Chicago’s West Side and in Englewood, contract selling stripped Blacks of three to four billion dollars in wealth over two decades, a University of Illinois-Chicago study found.

Nor did most Black veterans have equal access to Veterans Affairs (VA) home loans given out after World War Two. These loans were guaranteed by the VA, but administered by private, mostly white lenders, and discrimination ran rampant. From the 1930s through the 1960s, two percent of VA home loans went to non-white veterans, even though 13 percent of World War Two veterans were non-white.

THE LEGACY OF SEGREGATED CHICAGO

Studies have shown that contemporary Black Americans still face pervasive discrimination in getting home appraisals, loans, and insurance. For example, Carl Gershenson, Lab Director at the Eviction Lab, told The Chicago Reporter that in the leadup to the 2008 Financial Crisis, white homebuyers were much more likely to be steered toward government-guaranteed 30 year mortgages. “Non-white families were steered toward riskier mortgages,” Dr. Gershenson explained, “so after the [housing] bubble burst, they were much more likely to default than otherwise similar white homeowners.”

The Financial Crisis hit Chicago particularly hard. Housing prices crashed, and, by 2010, 31 percent of Chicago homeowners owed more in loan payments than their houses were worth. Many Black Chicagoans lost their homes. Since the Financial Crisis, mortgage lending standards have tightened, further limiting access to homeownership.

Now, only 38 percent of Black households in Cook County own the homes in which they live, compared to 70 percent of white households. Black Chicagoans are substantially less likely to be homeowners than white Chicagoans in the same income bracket.

Discriminatory lending practices do not just harm individual borrowers. The effects of these policies and practices are felt for generations. If a white family received a home loan in the 1930s, 40s, or 50s, the family could hold that home for decades, accumulating wealth to pass on to generation after generation. By contrast, a Black family denied a loan in the same time period would have neither the home nor the financial stability it would have provided.

Owning a home provides the ability to plan long-term and to borrow against your house, along with improved safety and health, Dr. Gershenson emphasized. Owning a home is also the typical way to accumulate wealth: because of those 30-year guaranteed mortgages, homeowners essentially live in rent-controlled housing, Dr. Gershenson explained. When interest rates go up, houses are not refinanced; renters, however, see their monthly payments increase.

Adjusted for inflation, the average home price in Illinois increased by almost 400 percent from 1940 to 2000. White families’ homes grew in value by hundreds of thousands of dollars, while many Black families can no longer afford the homes they could once have purchased if not for segregation and discriminatory lending.

CHICAGO’S GEOGRAPHIC RACISM

Urban Renewal legislation in the 1940s and 1950s gave the City of Chicago expanded powers to seize property for slum clearance and neighborhood “rehabilitation.” Major city institutions like the Illinois Institution of Technology, the University of Chicago, and Mercy Hospital expanded into neighboring communities. In a 15 year period, more than 80,000 Chicagoans were displaced. Many Black Chicagoans were moved to new, crowded public housing that was essentially segregated.

This reimagining of the city was made possible because Black homeowners’ voices carry substantially less political weight, Dr. Winling said. “There are a number of redlined areas of Chicago where the area description says ‘this area is blighted and should be redeveloped’ and then fifteen years later, it’s been redeveloped.” Black Chicagoans had little say in this transformation.

The Dan Ryan Expressway, opened in 1961 and expanded in 2006, runs straight through the length of the Black Belt. Its construction required the demolition of a number of Black neighborhoods, and the forced relocation of their residents.

Black Cook County residents, relatively powerless and forced into certain neighborhoods when they arrived in Chicago in the 19th century, were just as powerless when the City forced them out of those neighborhoods in the latter half of the 20th century.

This history of covenants, redlining, and renewal reveals the centrality of geography to inequality in Chicago. “Much of society is structured to discriminate against people who can’t afford to live in privileged zip codes,” said Dr. Gershenson.

“I would say 99 times out of 100, the grade distributions in the HOLC maps matchup pretty closely with whatever measure of contemporary inequality you want to look at,” Dr. Nelson said. Indeed, statistical analysis site FiveThirtyEight found that in Chicago, zones that were once rated “Best” by HOLC are now home to only around a third as many Blacks as zones that were once redlined. In Chicago, the higher rated a zone was in the 1930s, the whiter it remains today.

Houses that were once in Chicago’s “Best” zones now have a median home value of $937,000. Houses that were once redlined now have a median home value of only $323,000.

That is to say, Chicago’s financial inequalities are geographic in nature—and have roots which reach back hundreds of years. The legacy of Chicago’s relationships to its minority communities—Black, Indian, Mexican, immigrant—is a legacy of segregation and marginalization.

MOVING FORWARDS

This article on the historical roots of inequality in Chicago is part of a series that The Chicago Reporter is producing on financial health in Cook County. Future articles will dive deeper into housing, credit, and debt, among other topics.

If you are a Black, Latinx, or indigenous resident of Cook County who has struggled with daily expenses, debt, homebuying, or other aspects of financial health, or who has lived experiences of financial racism and segregation, The Chicago Reporter would love to speak with you to better inform our coverage. Please, send an email with your interest and a brief summary of your experience to: lntrottie@chicagoreporter.com. We would be happy to keep any identifying information confidential.

To learn more about the history of redlining in the United States, and explore redlined Chicago, can check out Dr. Winling and Dr. Nelson’s Mapping Inequality project here.

To learn more about racial covenants in Chicago, check out Dr. Winling’s Chicago Covenants project here.

To learn more about the link between geography and environmental quality, check out the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJSCreen here.

You can find FiveThirtyEight’s analysis of the contemporary racial makeups of previously redlined neighborhoods here.

You can find an interactive map showing the extent of the 1919 Chicago Race Riots here.

You can find out more about Eviction Lab’s work here.