“I’ve had many really beautiful experiences. But that doesn’t mean that my gas wasn’t cut off over the years, or that I didn’t get my car repoed once or twice,” Dorian Sylvain said, laughing.

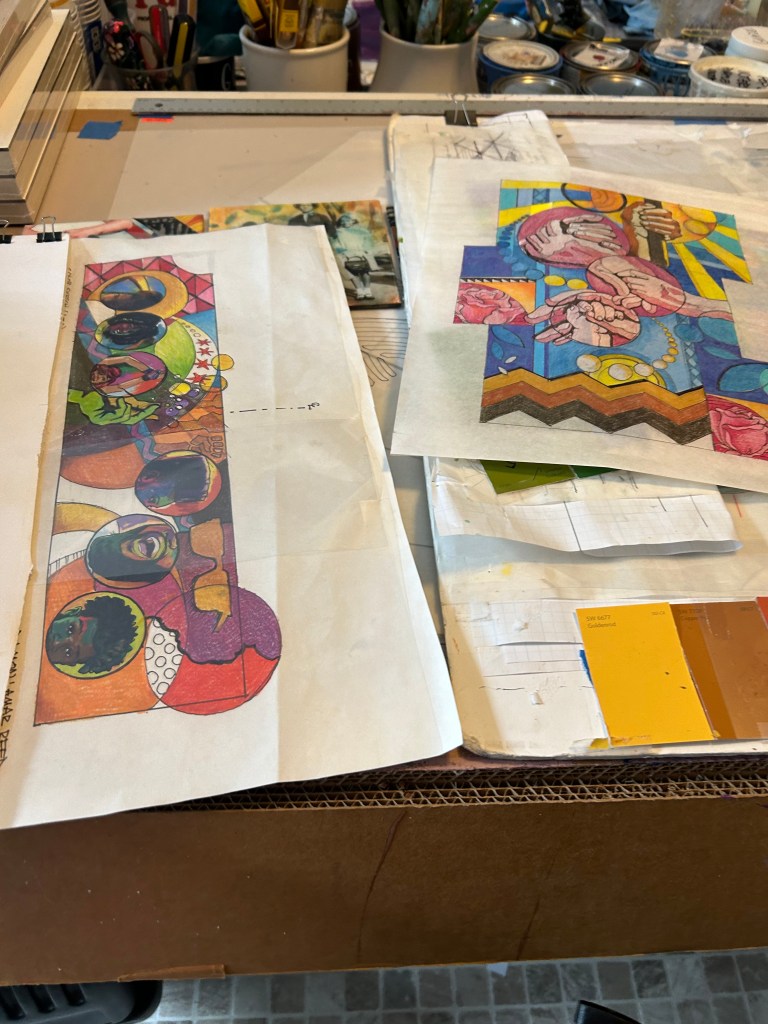

The Chicago-based multi-hyphenate—artist, curator, and educator—sat behind a desk in her light-soaked Kenwood gallery, surrounded by scattered canvases and paper collages like an exemplary creative powerhouse.

Sylvain “claimed being an artist” —her own words—in high school. What came next were two years at the American Academy of Art, a local commuter school, to earn an Associate of Fine Arts. After an especially bitter Chicago winter, she fled to San Francisco to get her bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary arts.

“It has always been a part of my life. My mother is not an artist, but she’s a real arts lover,” Sylvain said, “and she really made it her business to expose us to all kinds of cultural environments.”

Today, Sylvain works primarily with water-based paint. Her creations are heavily influenced by her experience painting scenery and integrate themselves seamlessly into Chicago cityscape. Some are meant to make a beautiful space, featuring floral motifs and patterns. Others touch on bigger topics, like a mural designed by her son mid-pandemic titled “Stay Home, Make Art.”

“I was always enthralled by the costumes and the scenery, and I had a little foundation in sewing from taking classes at the YMCA,” Sylvain said, “but there was something about the scenery that just really blew my mind.”

The artist got her start as an intern at a Black community theater, which fostered her interest in the relation of art to its surroundings.

Aside from these foundations in large-scale artwork, the theater also taught Sylvain about something that would become integral to her own art: community.

“The theater for me was really foundational as an artist because it not only was a place that I learned the most about collaboration, but I also became very grounded in the idea of community politics and the need for certain stories to be told,” Sylvain said.

“When I was coming up in the seventies and eighties, you didn’t see Black people on TV,” Sylvain said. “To (see) the politics of being in a Black community theater, which reinforced Black stories, Black identity, talked about Black history, Black heroes and ‘sheroes,’ it was huge.”

Sylvain moved into mural work to embrace this idea of sharing her advocacy and perspective. She continued to draw on her fascination with manipulating space as well as her devotion to the neighborhoods around her.

“I think that one of the things that excites me about murals not only is the scale, but I think it’s kind of like taking ownership to a neighborhood,” Sylvain said.

“You know, most people, most neighborhoods we live in, they’ve gone through different populations, so you’re inheriting it,” Sylvain said. “How do you claim it as yours? How do you make the public space a reflection of the community that’s there?”

This mission drives Mural Moves, Sylvain’s community-focused art initiative. The project grew out of Sylvain’s paints with her sons and local emerging artists, all tied to the idea of reclaiming space within the community.

The project got its start in earnest during the pandemic, when Sylvain, her sons and community members transformed boarded-up windows into murals. Part of her aim was to provide a training ground for young people interested in becoming public artists.

“I was thinking of it as an arts movement on the South Side,” Sylvain said. “I grew up in South Shore and I’m still very active in the South Shore neighborhood, and it just felt as though we didn’t use public art enough in the neighborhood that there were some really good opportunities to celebrate.”

Over the past four decades, Sylvain has worked mostly as a freelancer, hopping from one project to the next while rearing three children. This lived experience, much to her surprise, shaped her into a role model.

“I’ve talked to many young ladies who over the years have said, ‘We saw you doing it while you were dragging these three kids around with you, and so I knew I could do it too.’ That level of example can never be underestimated,” Sylvain said.

Sylvain also mentors high school students, who assist her by cutting stencils and filling in blocks of color. No matter how small the task, she said, these students are receiving an education in the arts that would otherwise be unavailable to them.

“The idea of Mural Moves is so important (because) on the South Side, we really live in what I call an arts education desert,” Sylvain said. “And there has not been a public project that I’ve ever worked on where I haven’t had at least one parent come up to me and say, ‘My daughter loves painting. How could she get involved in this?’”

The arts education desert that Sylvain references and actively works against is one barrier in the way of young people looking to get into street art. Perhaps even more impactful is the criminalization of this type of work.

City government banned the retail sale of spray paint in 1992 as a way of preventing vandalism, with Alderman Edward Burke, 14th, deeming spray cans “weapons of terror.”

“People do have a certain impression of spray cans as being the bad boy in art,” Sylvain said. “Even for myself, I had to learn to distinguish graffiti from spray can art, which are two different things, but people immediately associated it with graffiti, which they think of as messing up buildings and being a nuisance.”

Nowadays, street artists work to distinguish themselves from taggers, or those who use spray paint to mark their territory through the repeated use of a signature or symbol. This form of expression draws a stark contrast to the purposeful, aesthetic-driven work by artists like Sylvain.

“The stigma, it’s really interesting because when people see me with brushes versus a spray can, they respond very differently,” Sylvain said. She admitted that she used the term “graffiti artist” as a catchall for herself before she was corrected by her peers.

However, the pursuit of legitimacy often becomes a matter of “us versus them.” According to Sylvain, novice artists have historically used graffiti as a way into the street art scene, attaining foundational skills before producing more developed work, but this bridge has grown weaker.

She actively works to counter these setbacks, serving as an educator and regularly exposing people to the process of making art as a facet of community engagement.

“We are so removed from the process these days in 2023. We don’t even know how our clothes are made. We don’t know shit,” Sylvain said, laughing.

“But when you have a public artist working on site and you see the wall being power washed and then the next day it turns white and then the next day you see lines going up and then you start seeing color added…that is such a treat for the average person to witness,” Sylvain said. “It’s like public theater.”

Sylvain’s paints demonstrate their understanding of the communities in which they are seated. Some call the neighborhoods out directly, like a pastel-themed mural reading “South Shore Strong” in thick block letters.

The artist also organizes public paint days where she leads community members in composing a unified vision. In July 2022, she hosted an event where participants painted adinkra—Ghanian symbols representing concepts and proverbs—that were absorbed into a larger mural.

However, as much as she values public-facing art, Sylvain recognizes the role of advancing her creative process through more personal work, ensuring that the themes driving her art don’t get lost.

“I am really trying to be a little reflective, like, ‘What do those social movements mean? What does parenting mean?’” Sylvain said.

One example is last month’s exhibition, “A Dorian Sylvain Family Affair,” a collaboration between the Museum of Contemporary Art and Blanc Gallery that featured conversations, performance, and dance from a group of Black creatives. The event took place over a single day at a gallery in Bronzeville, the former home of luminaries like Ida B. Wells and Louis Armstrong.

“It is rather liberating not to have to meet people’s expectations, you know?” Sylvain said, explaining that she had not spent much time doing studio work. “Most of my work has been commissioned, so this is kind of a moment for me to be able to say, let me just have fun and do the kind of things that I want to do.”

She hopes that other artists find the courage to believe in themselves—after all, if she could do it, juggling her responsibilities as a mother while advancing her artistic career, others can too.

“To be able to raise my boys in the context of being a working artist, it’s not common,” Sylvain said. “And when I talk to young artists, one of the things that I try to really reinforce in them is the idea that you are the creator of your life. You get to make these decisions. You don’t have to go down one road, you know?”

“All Children Draw” is currently on view at Blanc Gallery. The exhibition focuses on the artistic dialogue between Sylvain and her sons Kahari, Kari, and Katon Blackburn. It explores the way her career has been influenced by the Black Arts Movement, and how that informed her sons’ artistic practices.