Monique Banks-McGee had been trying to sell her family home for months before she received a letter stating that the property could be acquired for the extension of the Chicago Transit Authority’s Red Line. The frame house she currently rents out in the Roseland neighborhood is along a proposed path of the massive transit project.

“We have not done an appraisal on the home, but the asking price is $35,000. If you look at the market in that area that’s what they are worth and less,” said Banks-McGee, whose parents bought the house 50 years ago.

The original purchase price has long faded from memory.

“It is a blow to our family because we didn’t expect the market to shift. The house that we grew up in, lived in … is worth nothing,” she said. “And we’re constantly being asked to reduce the price to sell it.”

The house is among more than 200 properties in Roseland, Washington Heights, West Pullman and Riverdale that could be acquired by the CTA to make way for the $2.3 billion project to expand the train line to the city’s southern limit.

Today is the last day for public comments on the two proposed paths for the Red Line extension. The transit agency and Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced on Sunday that it will invest $75 million to determine the placement of the line, part of a requirement to apply for $1 billion in federal funds to help pay for the project.

Some residents in the predominantly black communities affected by the extension support the project because it could increase access to public transit and bring jobs and economic development to an area that needs all three. But for homeowners like Banks-McGee the economic benefit is uncertain. The city’s history of residential segregation means that houses purchased decades ago have appreciated little in value. Coupled with the recent housing crisis, experts say homeowners may gain little if their homes are taken to make way for the Red Line extension.

Banks-McGee and most of her family moved to Atlanta years ago, but her former neighbors could be affected.

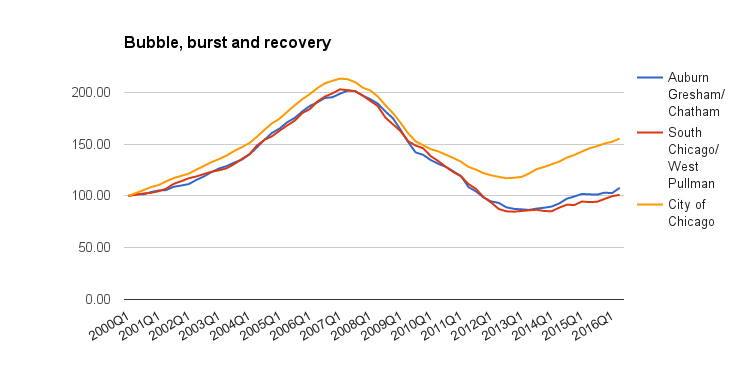

Under federal law, government agencies that acquire land for public use must at least pay fair market value for the property. But fair market value means little in communities where property values never really picked up after the housing crash. Despite a modest recovery from the darkest days of the real estate market, homes in Roseland, Auburn Gresham and neighboring communities are selling today for mid-2001 prices, according to historical index data from the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University.

Citywide, Chicago homes are worth about three-quarters their bubble-era peak – and steadily closing that gap. But Far South Side homes are recovering far more slowly, selling for only half what they would have fetched a decade ago.

Home prices in Roseland, Riverdale and other Far South Side communities fell further during the housing crisis and recovered more slowly compared to the rest of Chicago. This line chart shows the relative change in home prices since the year 2000, indicating that the city stands to pay historically low prices for properties in the way of the Red Line extension. (Roseland is included in the Auburn Gresham/Chatham group.)

Source: Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University

The situation may benefit the CTA, but not homeowners, who will see little for their investment– and have little to leave their children.

“One of the ways we can share wealth is to leave a legacy for our children and that legacy would be in ownership of a home,” said Margaret Wooten, the Chicago Urban League’s senior director of housing and financial empowerment. “The value of the home is part of the legacy you are leaving for the generation behind you.”

Fair market value in a neighborhood that is depreciating

Shari Henry’s parent’s bought their family home in 1970 after leaving the Dearborn Homes housing development.

“It was my parents’ first home,” said Henry, who moved back to Chicago nine months ago after her husband died. “It was a major accomplishment for them to move. It was at a time where many families were moving farther south into their own homes after living in public housing, and my parents were one of those families.”

The home Henry and a younger sister grew up in is on the east side of the Union Pacific railroad tracks; the Red Line could be built on either side of the tracks. The east side has more residential property; the west side has more commercial property.

Henry received CTA’s letter about the property, but she wonders if building the line is the right decision. The area, she said, has lost population, with schools sitting half empty and few businesses needed to support the line’s extension. Bus rapid transit, she said, could be a more cost-effective option.

“It is not an area that is thriving, that is in desperate need for transportation,” Henry said. “So to have a house destroyed for something that is not needed is what is bothersome to me.”

She’s unsure how the project will affect her property value. That’s not a concern for her or her mother right now since CTA has not made a final decision on the line’s placement. But Henry knows the homes in this area have depreciated, a situation she blames on blight and a slew of abandoned homes.

“My mom’s taxes are less than $10. She is a senior, but that just really shows how much property values have dropped in this area,” Henry said.

Just across the tracks, Bonnie Cannon breathed a sigh of relief. Her home was spared thanks to a grassy parkway that could be the site for the line’s west side option. Still Cannon is concerned for her neighbors, many of whom are retired seniors and have owned their homes for decades. Eleven years ago, Cannon brought her brick bungalow for $159,000, but she said the market value now is $20,000 less than what she paid for the house.

“They are not going to get what they paid for the house,” Cannon said of longtime neighbors whose houses may be purchased for the Red Line extension. “Some might get the value of the house because they didn’t pay that much back then. Those who are buying now are not going to get that back. I know if we sell our house today or tomorrow we would not get the value of what we paid for.”

The transit agency is a long way from acquiring property, but officials said they hope to negotiate with residents to purchase property. Federal law requires fair market value at the time of purchase, and in some cases, the original purchase price, transit officials said. The law also requires relocation expenses for any displaced homeowner, renter or business owner.

“If there are properties whose market value is significantly lower than what the original purchase price was, there are ways to make up the difference in the property acquisition, but that, again, is on a case-by-case basis,” said Brian Steele, a spokesperson for the Chicago Transit Authority. “We are so far from that actual point it is difficult to say what impact would come to play on those types of negotiations.”

Transit’s effect on property values

Studies have shown that on average property values near transit tend to increase, but that depends on different market forces, said Dena Belzer, president of Strategic Economics Inc., a California-based urban economics consulting firm specializing in transit-oriented development.

Her group conducted a 2008 study that showed that property values of single-family homes near transit increased between 2 to 32 percent.

“I don’t think there is an average,” she said. “I think it’s more realistic to say that transit in general does have a positive impact on property values, but the amount of that increase is quite variable.”

Areas suffering from low home values for a long time may not see an immediate bump. Instead, home values may increase steadily many years down the road.

That happened when a light rail line was placed in a mixed-income, multiracial community in Los Angeles. The rail was built in the 1980s, but the area is just now seeing an increase in property values, Belzer said.

Transit alone doesn’t increase property values. There must be coordinated planning and policies that complement transit, she said. Cities must have good zoning policies that allow higher-density residential development to spur transit-oriented development. To maximize public transit, the stations must be safe, clean, walkable and bikeable, and they should offer easy passenger drop-offs. Belzer said train frequency that links riders to their destinations is a no-brainer.

For Far South Side communities like Riverdale that are cut off from frequent public transit, extending the Red Line could improve residents’ access to jobs. On the other hand, the extension has the potential to spark gentrification that could displace long-term residents. That happened in Portland, Oregon.

Portland built a transit line through an economically depressed black community that resulted in an “uptick in housing prices or upscaling.” Black families were pushed out and “white hipsters started moving in,” said Janet L. Smith, co-director and associate professor of the Nathalie P. Voorhees Center, which advocates for comprehensive community development.

Whether this could happen to Roseland is hard to say, Smith noted.

“You should anticipate that [property values] might go up such that families will be impacted,” she said. “Positively, because they can sell their house and make some money. Negatively, they don’t have the income to cover the higher taxes.”

But there are ways residents can preserve affordable housing—tax relief for homeowners, caps on property taxes, especially for fixed-income individuals, and rent subsidies.

Banks-McGee said she doesn’t want her neighbors to be taken advantage of by the Red Line extension. “There are still people living there, whether they don’t want to or can’t afford to move,” she said. “For them to be able to pick up and move somewhere, they would have to get fair market value for their home.”

This story is part of a series examining how the proposed Red Line extension will affect residents on Chicago’s South Side. Sign up to get these stories in your inbox.

Thanks to the independence of service boards, lack of coordination, and a bit of turf mentality, the option of implementing CTA service on the nearby Metra Electric was never seriously explored as an option to extending the Red Line for $2b. This was first proposed over a decade ago as the Gray Line by means of a CTA purchase of Metra Electric service to South Chicago and Blue Island requiring money only for fare equipment for initial implementation. This proposal offered connectivity and integration with south suburban Metra and NICTD services as well as serving major lakefront destinations. The Gray Line would use existing infrastructure without need of residential displacement. Furthermore, the Rosemoor, Pullman, and Roseland neighbohoods developed around what is now the Mainline portion of the Blue Island Branch that also serves Stewart Ridge and West Pullman. Current Metra service has been reduced due to ridership diversion from less costly CTA bus and train fares; but that would change with CTA fares for Gray Line trains.

Thanks for your comment. Metra has to get on board with better fare integration, starting with accepting the plastic ventra cards and secondly Metra needs to devise a transfer system where riders are not charged full fares twice to go from CTA to Metra or vice versa. See our article on efforts to revamp Metra Electric: http://chicagoreporter-newspack-3.newspackstaging.com/revamped-metra-electric-could-put-south-side-on-the-fast-track/

THANK YOU Harvey — for your fine description of the benefits of the CTA Gray Line Project: http://bit.ly/GrayLineInfo One of the most important being that it would require NO [repeat NO] taking of any property at all, as the proposal utilizes Metra Electric District rail infrastructure

already in operation on the South Side each and every day.

All of the Chicago transit agencies — CTA, Metra, RTA, CMAP, IDOT, and City Hall – are very

well aware of the Gray Line Project; but they suppress the idea (along with all the Chicago area major Media — TV and Newspapers) — as it wouldn’t put $2.3 Billion dollars in the pockets of the

big Connected Construction Company Campaign Contributors who would build the Red Line Extension!

Here is a Side-by-Side comparison of the relative costs, and resulting benefits of the $2.3 Billion Red Line Extension, versus the $500 Million Gray Line Project: http://www.grayline.20m.com/photo.html

And the Gray Line could be in full operation in approximately one year, versus starting construction (maybe) in 2022 — with Red Line trains finally beginning operation on the Extension in 2026 (ten years from now).

Please contact me with comments, questions, or for information: grayline15@yahoo.com

We should not care about property values.

https://fanaca.wordpress.com/2016/12/05/winter-reading-list/