COVID 19 forces changes in strategies for anti-violence groups

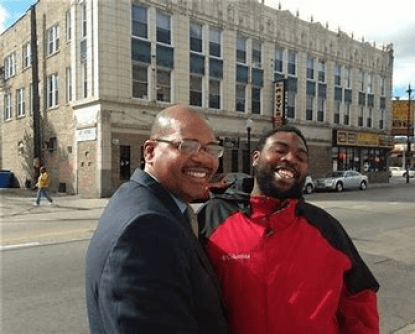

Like much of the country, Autry Phillips was caught off guard when a worldwide health crisis descended on Chicago last year. In addition to his long-time, ongoing efforts to reduce neighborhood violence, he now faced the challenge of conveying his organization’s message to residents who were increasingly vulnerable to a rampant virus.

“When COVID hit back in March we didn’t know what to do,” says Phillips, executive director of Target Area Development Corp.. “If COVID was part of a street organization and carrying a gun, hanging out on the corner, I would have known exactly what to do. We had no idea what to do with COVID.”

Aside from sharing federal safety guidelines to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (“We said, ‘It’s time to put the guns down, but you gotta put a mask on now,’” recalls Phillips.), he and other peace activists have been forced to regroup and re-strategize. In light of the alarming rate of Chicago violence recorded in 2020, including 792 deaths, Phillips is helping to implement plans that ensure 2021 brings more encouraging statistics.

While not all of last year’s killings, including seven reported police shootings, have been categorized as murders, Chicago’s 2020 homicide rate is roughly equal to the year-ending totals reported in Los Angeles and New York City combined. Chicago’s murder rate increased by about 50 percent from 2019, while LA’s homicides grew by 30 percent and New York’s grew by almost 40 percent. Including 3,455 wound survivors, 2020 was Chicago’s most violent year since 2016 when 808 were killed and 3,658 were wounded. Of 2020’s incident’s 53 children 12 and younger were shot, six fatally.

“We had a double pandemic,” says Phillips, echoing words some used to describe COVID-19’s outbreak and simultaneous nationwide racial eruptions.

Although the medical pandemic has continued into the New Year, Target Area is one of about 20 partners determined to stem Chicago’s violence. As part of Communities Partnering 4 Peace (CP4P), an initiative of Metropolitan Family Services, 23 neighborhoods will receive expanded conflict resolution and public safety support, beginning with a newly enrolled class of peace advocates.

“So we have found that this qualitative measure has really added value to the community in Chicago,” says Vanessa Perry DeReef, director of training at Metropolitan Peace Academy.

The Academy, which will launch its next cohort of 25 participants Jan. 26, is an 18-week fellowship that allows fellows to earn community education credits with the option to pursue degrees in social work and/or addiction studies at Kennedy-King Community College. Incorporating 14 working standards and 10 competencies that encompass a code of conduct and professionalism, Metropolitan Peace Academy’s objective is to train and qualify “street outreach professionals,” Perry DeReef says. About 150 men and women have graduated from the program, including fellows who began meeting and training in city parks after COVID-19 restrictions limited indoor gatherings last year.

“The communities they were working with were very heavily impacted,” Perry DeReef adds.

Fellows also added distribution of food and personal protection equipment to their community service, while abiding by such standards as avoiding controlled substances, establishing relationships with law enforcement, and advocating on behalf of families.

Now virtual, Metropolitan Peace Academy training is part of a vision launched by Metropolitan Family Services in 2017 to “professionalize” street outreach. Jowain “Joe” Washington, a Metropolitan Family Services field manager for southeast Chicago, says an added component designed to reduce violence in 2021 involves intervening between citizens returning from prison and residents of the 23 neighborhoods the Academy serves. The prison intervention stresses communication with incarcerated men and women whose influence in their neighborhoods is powerful enough to disrupt progress and dialogue toward non-violence, especially when the area’s violence is connected to activity that generates thousands of dollars a day.

“And now you get home and you’re making $1,500 every two weeks?” Washington asks, incredulously.

The temptation to “relapse” into violent behavior can be greater for incarcerated citizens returning home when they lack lifestyle alternatives like those CP4P’s member organizations provide, says Washington, a trainer with Metropolitan Peace Academy.

“It’s a collaboration of all these organizations with one goal, which is to stop the shootings,” he adds. “Now it’s four goals, four pillars: trauma-informed, hyper-local, professionalism, and restorative justice.”

CP4P’s original goal helped shape the Academy’s curriculum and its recruitment of fellows.

“They teach you everything like how to go out and do mediation, violence prevention,” Washington says. “Their main thing was finding people who were already in the community doing the work instead of getting somebody from outside the community to come into the community.”

As with most non-profits, funding remains a key challenge in the work of “credible messengers” and “violence interrupters” that he and others train, says Washington. Chicago’s 808 killings in 2016 were largely a reflection of budget freezing and lack of resources compared with those available the previous year, he adds. Known for increased rates of violence in July, the city’s 7th and 11th Districts were targeted for a peace campaign in 2015, resulting in not a single shooting during Fourth of July weekend, the first such achievement in about 20 years. There was only one shooting the entire month – but the next year’s skyrocketing violence and evaporated funding was no coincidence, says Washington. CP4P’s function as an umbrella for anti-violence organizations has enabled better funding distribution, he says, despite 2020’s incidents. He attributes the increase to an ongoing world event.

While many cities nationwide reported reduced crime rates during government shelter-in-place orders and business shutdowns due to the pandemic, Washington blames restlessness in parts of Chicago for violence that later erupted.

“People had cabin fever, man,” he says.

“When they did pop out, people were trying to get their lick back or deal with old rivals, that kind of thing. I believe the pandemic had a lot to do with it,” he adds.

Phillips is less certain whether 2020’s rash of killings stemmed from the pandemic, but he has observed a historical pattern of fiscal-year-ending budgets spikes in violence occurring at the same time. He says he’s encouraged by Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s commitment to funneling resources to non-violence agencies, which Phillips believes demonstrates more support than that of previous mayors.

“We still need additional funding because all the areas in the city of Chicago are not covered,” he says.

But CP4P’s model has helped unify and better position member organizations like Target Area by incorporating across-the-board techniques for operating and educating the community.

“We’re not in silos any more,” says Phillips.

Like Washington, he also expects the CB4P prison outreach component to yield dividends in 2021 by persuading returning citizens to seek legal, more viable alternatives to community re-entry.

“So instead of going back to the clique or going back to the guys on the corner, we’re giving them a chance to change their lives,” he says.

CB4P’s strategies reflect innovation and show promise, according to best practices among similar programs. While programs like the Urban Peace Institute in California and the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York offer aspects of conflict resolution, academic development and wrap-around, family support like the services CB4P incorporates, the Chicago-based emphasis on formalized anti-violence training is less common.

But one factor that’s too often overlooked in efforts to end neighborhood violence is the lack of empowerment, says LeVon Stone Sr., CEO of Acclivus, Inc. He sums up one of the key elements to reducing Chicago’s 2020 homicide rate with one word: “Opportunities.”

The landscape of community organizations specializing in non-violence often consists of white fiduciary agents overseeing the operation and advocacy of more qualified program leaders, Stone says.

“My plan for Acclivus is to work with 12 Black grassroots organizations, and what we’re focusing on is giving more common folks the opportunity to do something in their community,” he adds. “I don’t believe people think about how much different it could be if it’s Black-owned. When people feel invested they appreciate things more.”

Along with its community presence, Acclivus incorporates a hospital response program in partnership with five level-one trauma centers in the Chicago area, dispatching a team member to meet with victims of violence or their families, in order to de-escalate tension. As in the recent case of a “high-profile” rap artist in the community, hospital intervention by Acclivus helped prevent retribution for violence that led to the artist’s death, Stone adds.

“We played a major role in de-escalating it from spilling out into the community again,” he says.

His goal is to use the organization’s public health model and methodology as a means of training and expand the field for Black anti-violence program leaders. Acclivus’ staff and leadership is predominantly Black and includes team members from many of the neighborhoods in which they work, “not only having that lived experience, but having that scholarship to be able to address some of these challenges,” Stone says.

Meanwhile, Chicago law enforcement relies on the expertise of experienced organizers like Stone and hopes to receive continued support from peace advocates through 2021.

“The Chicago Police Department has shifted away from a law enforcement first and only strategy, and understands the importance of finding solutions to underlying issues that may lead to violent crime,” says Maggie Huynh, a department spokesperson. “CPD’s crime-fighting strategy is an effort that not only focuses on traditional policing, but also focuses on our partnerships with block clubs, community-based organizations and street outreach organizations in neighborhoods citywide.

“Violence prevention organizations are critical to this effort, as they work to address the root causes of violence and provide services such as crisis de-escalation, employment in transitional jobs and cognitive behavioral therapy and support for those who are most vulnerable. CPD continues to work together with our community partners and organizations to make Chicago a safer city.”