Catalyst Chicago, dedicated its Summer 2014 issue to examining how the War on Drugs is playing out in Chicago’s public schools. This article is the first in a series that highlights how education officials are quick to call police to deal with misconduct, leading to harsher punishments than an adult would face for the same offense. Meanwhile, a new loophole in Chicago Public Schools’ code of conduct could put more students on the path to expulsion without a hearing.

It is a week and a half before school lets out for the summer, and though the weather is on the cool side, children are on the playground of Little Village Elementary School, shouting and running in the late afternoon.

Anthony Martinez slides into the basement of an old building on the corner across the street. Several teenaged boys are slouched on a worn, weathered couch, playing video games in the dim light. Others are shooting pool. The young men are here as part of Urban Life Skills, a diversion program that allows young offenders to avoid the juvenile court system and a possible criminal record.

Anthony, who is the youngest in the room, sits by himself. He looks nervous in the way a 15-year-old might, staying quiet and biting his lip. Short and with a bit of a round face, Anthony sports a small gold earring in each ear, and today wears what is something of a uniform for teenage boys in the neighborhood—an oversized white t-shirt and too-baggy blue jeans.

Anthony is supposed to be getting ready for his eighth-grade graduation from Kanoon Magnet Elementary, but he is not sure that it will happen. His math teacher is threatening to fail him, and he could be forced to go to summer school.

If so, that would derail his high school plans: Anthony wants to go to Community Links High School, a year-round school that allows students to graduate in three years. It is smaller than most high schools and would give Anthony the individual attention and fresh start he so desperately wants.

But Community Links requires students to be “in good standing” in order to enroll, so Anthony will lose his chance if he fails eighth grade. Instead, he would be stuck at Farragut, his neighborhood high school. Though Farragut’s dean of discipline says the school environment has become calmer and there is almost no gang-banging, Anthony says he knows too many other young men at the school and would come in with too much negative baggage.

“I am trying to have a better life, but if I went to Farragut, I would probably drop out,” he says.

Anthony, the younger brother of a known Latin King gang member, says that the teachers at Kanoon never liked him, always thought he was a bad apple and for years considered him “at-risk.” Mostly, he maintains, the teachers dislike him because of the incident that led to his arrest and his eventual assignment to the Urban Life Skills program: a playground fight that he was accused of participating in and breaking a girl’s nose.

Anthony insists he had nothing to do with the fight. Initially, he was only suspended; it wasn’t until weeks later that police came to the school to arrest him. Fearing he would be found guilty of aggravated assault, Anthony pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and was placed on two years’ probation and sent to the Urban Life Skills program.

Art Guerrero, who runs Urban Life Skills and has volunteered at Kanoon, says the arrest probably happened because the girl’s father insisted some action be taken. Guerrero adds that Anthony has had problems with teachers being wary of him and that the school does tend to call the police a lot.

Like Anthony, many of the students arrested at schools are challenging and perhaps made bad decisions, but there are alternative ways to deal with them other than calling the police, says Joel Rodriguez, an organizer for the Southwest Organizing Project, which has worked with Voices of Youth in Chicago Education to advocate for a diminished police presence in schools. He notes that students are usually back in the school very soon after being arrested and nothing has changed about the circumstances surrounding the incident.

“Instead of dealing with human beings, we are just calling the police,” he says. “With all the stresses in schools, people have very little energy to deal with students.”

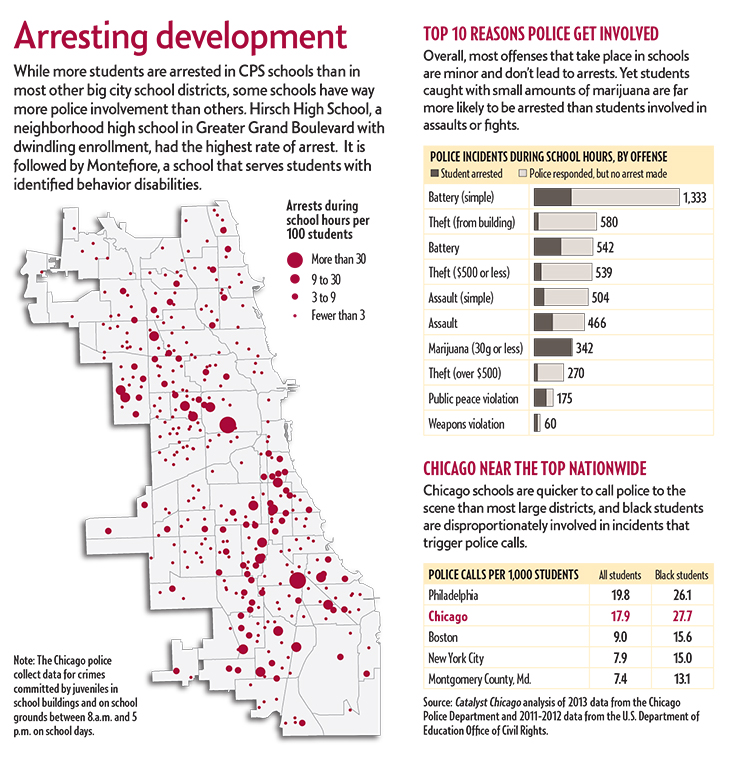

More so than in other large school districts, Chicago schools are quick to call in police to handle student misbehavior and conflict, according to a Catalyst Chicago analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights for the 2011-2012 school year (the most recent available). In Chicago, police were called at a rate of nearly 18 cases for every 1,000 students, while New York City’s rate was 8 per 1,000 students and numbers in Los Angeles were 6 per 1,000.

Overall, CPS referred 7,157 students to law enforcement, of whom 2,418 students were arrested, according to the federal data. As is the case with school discipline in general, black males are disproportionately targeted: They make up about 20 percent of CPS students, but 40 percent of those referred and arrested. Another 20 percent of students arrested or referred to law enforcement are Latino males—about the same percentage as Latino male enrollment. (Black and Latino girls are the vast majority of the other students who are referred or arrested.)

What’s more, these numbers likely underestimate the true number of arrests of young people in and around schools. The federal CPS data only includes incidents in which a school staff member calls police to the building. However, Chicago police track all arrests of those 17 or younger in a school building or on school grounds, regardless of how the arrest originated.

The Chicago Police Department reported 3,768 arrests of minors in schools and on school grounds during school hours in 2011-2012, according to data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

(In early July, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced that 1,000 fewer students were arrested in the 2014 school year, but the police department did not confirm these figures.)

Students are acutely aware of the heavy police presence in their schools, says Mathilda de Dios, program manager for Northwestern University’s Children and Family Justice Center. As part of her job, she leads Know Your Rights workshops at high schools and community centers.

At the start of workshops, she asks teens how many of them have been arrested at school or know someone who has been. More than 80 percent of them typically stand up.

Asked how many of them go to schools with restorative justice programs such as peace circles or peer juries, and about 30 percent stand up.

De Dios says that police involvement rarely leads to a resolution of the conflict. And when police lead students out of school in handcuffs, it shapes how they view school and how school employees perceive them.

Jennifer Viets learned this the hard way when her son was taken by police out of a freshman summer program at Lane Tech High. Viets says the police were only trying to get information from her son about his friend, who was accused of throwing rocks. But her son told her that when he returned to Lane the next day, teachers commented to him that they didn’t think he would be back.

A few years later, Viets’ son and his friend were led away from school in handcuffs after being accused of stealing at a party. Viets notes that the two were the only young black men at the party. They were never charged, as the investigation eventually pointed to other culprits. Nevertheless, Viets says her son was scared.

“Everything went downhill after that,” Viets says. Her son wound up leaving Lane and completing high school with a virtual charter school. His friend transferred out too.

“It changes the way everyone perceives you when you are arrested, even if you are never charged,” she says. “How do you recover from that?”

At Kanoon, where Anthony attends, 13 students were referred to police or arrested in the 2011-2012 school year. That doesn’t sound like many, but it puts Kanoon at the higher end of the scale for elementary schools: 68 percent of elementary schools had fewer than five incidents of police involvement, and the vast majority did not lead to arrests, according to the federal data.

Meanwhile, just 20 high schools accounted for half of all arrests —even though students in those schools made up less than a quarter of the high school population.

Most incidents that lead to police involvement are simple battery or assault cases, theft cases or possession of small amounts of marijuana, according to a Catalyst analysis of Chicago police data.

In June, CPS overhauled its student code of conduct and drastically cut the list of incidents that require police notification. The new code, which youth and parent advocacy groups had pushed for, now only requires police notification for drug or gun possession. In other cases, school officials can decide themselves whether or not to call police, depending on the severity of the crime and whether others were hurt or in danger of being hurt. Plus, principals must check with the Law Department before calling police on a student who is in fifth grade or younger.

In contrast, the previous code listed 27 categories of incidents that required a call to police, including battery and “any illegal activity which interferes with the school’s educational process.”

Yet Chicago remains an outlier. A Catalyst review of discipline codes from suburban Chicago districts and other large urban school districts shows that many give principals full discretion to decide whether to call in police, even in drug and gun possession cases.

Cliff Nellis, lead attorney for the Lawndale Christian Legal Center, says that too many young people come to him after arrests for incidents that could easily be labeled a misdemeanor or dealt with through school discipline. “In mostly white suburbs, it is almost always misconduct, whereas here it is a crime,” says Nellis, referring to the rough West Side neighborhood.

Nellis points to one case in which a client and his friend broke into their high school and played basketball in the gym. “It was basically a prank,” he says. The alarm was triggered and police wound up surrounding the school. The boys hid, but were eventually sniffed out by dogs.

Nellis says the boys had nothing in their possession and the only things out of place in the school were basketballs. “They could have been charged with misdemeanor trespassing and the boys could have had a call home,” he says. “Instead, they were charged with a Class 2 felony burglary—breaking and entering with intent to steal. The intent is subjective.”

Schools are only part of it, says Nellis. Arrests on the streets and in the schools start young for many and this involvement follows them into adulthood. More than 57 percent of adults in North Lawndale have criminal convictions, according to a 2002 Center for Impact Research study, a mark that makes it more difficult to get a job and do other things necessary to change the direction of one’s life.

“This neighborhood is flat-out oppressed by the criminal justice system,” he says.

Cook County’s Juvenile Justice Division reports that about 75 percent of young people on probation re-enroll in school, but not necessarily the same school they attended at the time of arrest. (As part of juvenile probation, students must enroll in school.) Those on the ground say many are steered toward alternative schools. CPS is in the midst of a major expansion of alternative schools, many of them to be operated by for-profit companies.

Elvis Aguilera found out the hard way how difficult it can be to re-enroll. Elvis just turned 16 in January, but he has already been in and out of the detention center three times and in-patient drug rehab programs three times as well. The last time he got out of youth prison in St. Charles on parole in October 2013, Elvis went with his mother to get back into Farragut High School. School officials, he says, told him to just wait. Every two or three weeks, he and his mother went back and asked for him to be let back in, only to be turned down.

Eventually, the staff at Urban Life Skills got involved and reached out to a re-enrollment specialist at CPS. (In 2013, CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett hired these specialists to look for teenagers not in school.) According to Elvis and Art Guerrero, they were given some surprising news: Farragut still counted Elvis as enrolled.

Sixteen-year-old Elvis Aguilera, center, shares a meal with other participants in the juvenile diversion program to which he was assigned. The youth meet on Friday evenings from 6 to 9 p.m. and participate in workshops on topics like perseverance. [Photo by Bill Healy for Catalyst]

The re-enrollment specialist told Guerrero that it is not unusual for schools to keep students enrolled, even though they are gone for months at a time. With high schools struggling to keep enrollment up because the district has switched to providing money on a per-pupil basis, it benefits schools to have these students on their rolls. But schools will quickly drop them when pressured to actually take them back, the re-enrollment specialist told Guerrero—schools don’t want teens perceived as problems or potential trouble. Elvis, in particular, has a tattoo that the principal didn’t like.

Elvis says that on his 16th birthday, he was officially unenrolled from Farragut. He says he was told he could try an alternative school or a GED program, but so far has turned down the idea. Now he spends his day helping walk the neighbor’s children to school and waiting for 4 p.m. when he can go to the diversion program. “I am so bored,” he says, noting that the last time he relapsed into drug use was because he was bored.

For Anthony, getting assigned to juvenile probation officer Elizabeth Marrero and placed in Guerrero’s diversion program felt eerily familiar. Both Marrero and Guerrero worked with Anthony’s older brother, Victor. Guerrero says he met Anthony when was he was about nine or 10 years old and would beg to tag along on field trips with the diversion program. Diversion programs often take their clients to ball games, museums or downtown.

Guerrero also volunteered at Kanoon, taking a group of “at-risk” sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders aside and talking to them about once a week. Anthony was part of that group. “I have known him since he was a shorty,” Guerrero says.

Guerrero’s life mission is to prevent others from following the same path he took. In his wallet, Guerrero, who is almost 50, has a picture of himself from 13 years ago. His face is sunken in, with deep wrinkles. His eyes have large swollen bags under them. He’s rail-thin.

Guerrero says he was just like these boys at one time. He grew up in the neighborhood and his grandmother still lives in the same house just a few blocks from the diversion program. He gang-banged. He smoked weed. He got addicted to heroin. He overdosed six times.

On September 25, 2005, Guerrero was arrested and charged with dealing drugs near a school, a Class X Felony. He was 39 years old, and faced between six and 30 years behind bars. “In jail, I was saved,” he says. “I felt like God was telling me that I had a purpose and it is not to be a dealer or an addict.”

After a year, he came out of prison and started volunteering with Urban Life Skills, which is connected to New Life Church, an evangelical church with several locations in Chicago. That is when Guerrero became involved in Anthony’s life. Guerrero’s face has filled out and now, he has a middle-aged pouch that makes him look healthy and normal. He likes taking Anthony and the other boys out to get something to eat. In the quietness of a car ride or over a taco or some ice cream, they’ll often talk to him about their fears and their hopes.

Guerrero says he gains the boys’ trust. Marrero says he plays good cop. “I play bad cop,” says the probation officer, a tall, thin striking woman. She says she has to be stern to let her clients know that she is about business. She is a mandated court reporter, so what she finds out she has to tell the judge. But she is also motherly.

Guerrero says that over time the drugs may have changed, but the cycle is much the same. Young teens, like Anthony, mostly smoke weed. But as they get deeper into the street life, they graduate to harder drugs. The addiction to drugs makes it more difficult to take a different path.

When Anthony first started at the juvenile diversion program, some drug tests showed he was smoking marijuana. But lately, they have come out clean.

Anthony is young enough and eager enough that he’s still got the potential to change his trajectory. That is why there was a palpable sense of relief on the Friday before graduation when he flew into the Urban Life Skills basement and announced that he was going to graduate. “The principal called me into the office and told me I could walk,” he says. “They gave me a gown.”

That evening the clients were treated to Mexican food, as well as a guest speaker to kick off the theme of the month: perseverance. One of the first things the speaker did was ask the young men if they knew the definition of the word. No one did.

“It means doing something despite difficulty,” says Arnulfo Torres, a counselor for Rudy Lozano Leadership Academy, an alternative school in Humboldt Park. “What happens when you walk down the street and you get jumped and you go to the hospital? What happens when your brother gets shot up? What happens to you? You keep living. Life still goes on. You don’t stop being what you are. You have perseverance.”

A few days later, Guerrero and Marrero attend Anthony’s graduation. They stand in the back behind the parents and brothers and sisters. They each came with different messages that they wanted to get across to him. Marrero wanted this to be special for Anthony. She wanted him to savor the moment. She kept pointing out to him how so many people were proud. “Even the principal gave you a real honest hug,” she told him.

Marrero watched him closely. She noticed that when all the other graduates tossed their caps into the air, Anthony reached up and held his firm on his head. Later, when she mentions it to Anthony, he says: “I didn’t want to lose it.”

Guerrero wasted so many years cycling in and out of prison and drug rehab and now spends his days trying to hold a life jacket out for young men, some of whom are destined to do the same. Guerrero knows that Anthony’s journey is not going to be easy. The message Guerrero had for Anthony is that he can overcome the assumptions and expectations that he won’t make it.

As he hugged him, over and over again as though repeating a prayer, he says, “This is just the beginning. This is just the beginning.”

“I told the principal that in the end, Anthony is going to prove everyone wrong,” he says, looking straight at Anthony. “He is going to graduate from high school. He is going to make it.”