Watching Chicago’s own Jackie Robinson West become the first all-African-American U.S. Champion of the Little League World Series in 30 years, Edward Thompson laughed.

“They’re very well organized,” the 91-year-old former Little League coach said. “It’s good for the kids. … They get a sense of what they can accomplish.”

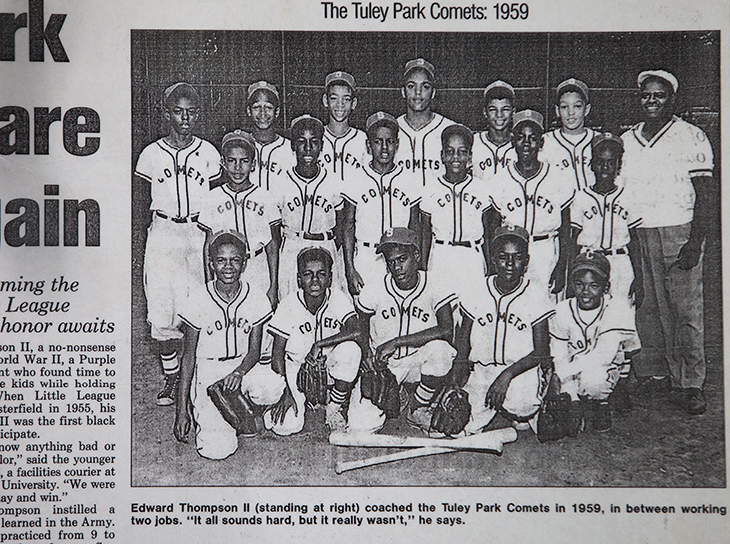

In 1959, Thompson led another group of Chicago boys – Chatham’s Tuley Park Comets — in a similar experience. They were the first all-African-American team to win the Chicago Park District’s Little League baseball championship, going undefeated at 32-0 that season. Their run also included winning the Thillens Stadium Tournament.

Pre-civil rights, the team was often confronted with bigotry and racism as they defeated several all-white teams.

Long-time neighborhood resident David Floyd was the team’s second baseman. Just 12-years-old at the time, he remembers only joy from those baseball filled summers and credits Thompson for shielding many of the players from the conflicts and tension of the era.

“To us it was just baseball,” Floyd, 67, explained. “He didn’t let the environment at the time change us; we changed it.”

Thompson, a World War II Purple Heart recipient, first volunteered to be a little league coach because the league had run out of teams.

“The longer I stayed into it the more I got involved,” Thompson, 91, said. “Next thing I knew I was head over heels in boys’ baseball.”

Today, Floyd, a former CTA bus driver, spends his spare time talking to local youth as part of Project HOOD’s outreach program.

The Chicago Reporter sat down with both men as they reflect on the legacy of the Tuley Park Comets and the importance of community activities for children.

How did the Comets start?

Thompson: My boy wanted to play ball. I thought he meant softball but he wanted to play league ball. I went to go sign him up but all the spots were filled. It was suggested to me, if I wanted to be coach, I could make a team. I volunteered. And there I was for the next four or five years.

[The director] let me know from the go that the best of the ball players had already been picked and that I would be left with the leftover players, which was alright. All I wanted was to get started. It just so happened that we won our first three games. We lost the rest. It was a good first year. It introduced us to Park District baseball.

What that also did was encourage the guys to come back for the next year. I ended up having the advantage in the league because I had the same guys coming back. They were a year older and much smarter at baseball. As a result I had the best team in the league.

Did the demands of coaching a team get to you?

Thompson: I would work nights and when I would come home, they’d be out here waiting for me.

Floyd: Yeah, we’d be waiting for you. We ran the grass of his house down. We were coming in and out of his house all the time.

Thompson: We’d practice all morning. Play in the afternoons. Then I’d go to work at night and right back around the next day. I would advise anyone who has the time that it’s worth it.

Did you have the support of the community?

Thompson: Yes, it was a new thing for the neighborhood. The families got together and organized a raffle to buy [the team’s] uniforms. The parents had fun and the kids had fun too.

Floyd: We had a father son game remember?

Thompson: Oh, yes, that was a fun game.

Floyd: Ernie Banks (former Chicago Cubs great) came out to help us.

Thompson: Yes, Ernie Banks would come out. He practically lived in the neighborhood. Helped the kids learn to bat.

What would you tell your players to encourage them?

Floyd: You would always tell us to go to school and get an education remember? You used to tell us that all the time.

Thompson: Yes, every chance I had I tried to stress that.

Floyd: Everyone wanted to play for you.

Thompson: Any chance I had to expose them to bigger and better things I did. We played in Thillens Stadium. We were the first team from Tuley Park to play up there.

A Chicago Sun-Times article from 2000 about the dedication of Tuley Park’s baseball field to the Comets hangs in the dining room of Edward Thompson, the team’s coach. David Floyd, who played on the team, describes how the boys were always at Thompson’s house, “we made that place a dust bowl,” from always running through and treading on his grass. [Photo by Michelle Kanaar]

In one game hot dogs were thrown at one of your players by someone in the stadium? How did you react?

Floyd: Dwight Harris (catcher) was hit with a hot dog, remember?

Thompson: Well, like anything else, everybody was shocked but it happens. They never had anything like our team before. We were reading about [the issues] in the papers but never experienced it.

We weren’t the first black team to play [in Thillens], but we were the first black team to win out there.

What did that win mean to be the first?

Thompson: At the time it was just a ball game, but as time went on we were recognized for being the first to do it. The mayor had [the players] downtown. That was fantastic. They all had a great time down in City Hall. I did, too. I enjoyed it!

Note: In August 2000, the baseball field of Tuley Park was renamed, “The Comets” to honor the teams’ accomplishments.

Why did you stop coaching?

Thompson: The kids moved on up. No one else came behind them.

Today people are complaining about crime, you know? Kids have to do something. As a rule, each group of kids comes along and has their own thing. If the next group has something to follow and it’s good, that’s good. But if there’s a void, anything might fall in there, good or bad.

Kids really do decide the direction of a neighborhood. They need something to keep them occupied.

What is it like to grow up in Chatham now compared to your time with the Comets?

Floyd: It’s rough. I understand now how important it was for us to grow up and have a mentor. My brothers and I, we would go to [Thompson’s] house and say thank you. Because we would go through his front door and out the back. Go through his fridge. He’d take us to the park and practice with us. Children lack mentors now.

How do kids today react when you approach them to talk to them?

Floyd: They listen. You’d be surprised. They are out on the basketball court; maybe after the game is over I’ll converse with them. What I’ve noticed is there’s as many girls as there are boys who need more guidance. They are out here trying to run their own lives. This young generation, they don’t look for advice or think about the consequences [of their actions].

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.