In March of 1965, captivated by the images coming out of Selma, Ala., of demonstrators being tear-gassed and attacked by police, then-Roman Catholic priest Bernard Kleina joined the civil rights movement.

“I was responding to what I saw on TV,” Kleina said. “I really didn’t know what to do, but I knew I had to do something. I first flew to Montgomery and then to Selma to see what I could do to right the wrongs that were going on at that time.”

A lifelong activist for social justice, Kleina spent much of the ’60s on the front lines of demonstrations. After he retired from the priesthood, he spent 41 years as the executive director of the HOPE Fair Housing Center, in Wheaton, Ill., an organization that fights housing discrimination.

But no matter his activism, Kleina’s camera has always been nearby to capture the struggles and efforts of those working towards equality.

“I’ve always been a photographer,” Kleina, 78, said. “I was always able to combine my photography with my activism.”

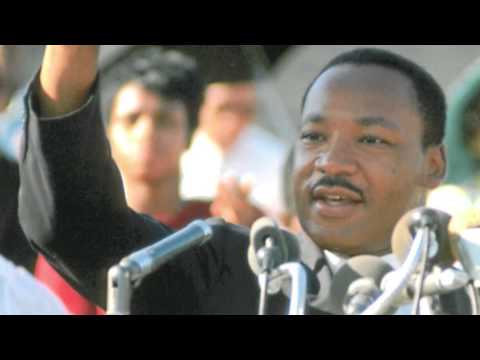

That ability made Kleina one of the few photographers to have captured colored images of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on film.

The Chicago Reporter sat down with Kleina and talked about his time in the civil rights movement, and how he wants his photography to one day be remembered.

You were a priest at the time, what did your fellow priests say to you about the work you were doing?

Most of them said nothing, which I thought was pretty sad. The bishop was typical of bishops at that time, they didn’t really approve of priests being involved. But on the other hand they couldn’t stop me or stop others from being involved in these marches.

Were people surprised when they saw you — a white priest — at these marches?

Well, at least in Selma I think everyone knew why they were there. The focus wasn’t on anyone or any individuals, but rather what we were trying to do. [Note: Dr. King summoned clergy to Selma after 17 marchers were hospitalized in a clash with Alabama authorities the week before.]

At the time, voting rights was one of the key issues. Each day we would go to the brown chapel where we were instructed on what to do and what not to do. I spent more time in church in Selma than I ever spent as a priest in my parish.

Were you ever hurt?

There was a time in Selma. We were instructed where to go for lunch and I wasn’t paying attention. There were guys at a tire shop. They were hitting their hands with tire irons and showing me what they wanted to do with me. We had to take them very seriously because the week before Rev. [James] Reeb was killed in just that way in Selma.

What were your conversations with the folks down there like?

There was a certain amount of frustration and trying to figure out the best approach to get our message across.

What was your experience, when these demonstrations moved to Chicago?

From my experience — it was limited, certainly — but I found Chicago to be more brutal than Selma.

What are some examples of that?

One time, particularly in Marquette Park, I went to photograph what was going on. But when I saw the huge crowds of people outnumbering the demonstrators I realized I had to join in. I put my camera away and got in the march. There were huge crowds of people spitting on me and everybody else involved. The crowd was throwing rocks and bottles at us.

Many people in the march had to be taken away by ambulance. It was a brutal time. What I found ironic was, in marches like that, I was dressed as a priest and I would see kids wearing Saint Rita or Saint Leo sweatshirts and I would think, “There is something wrong here.” It was a particularly tough march for me.

Dr. King came a week later, and when he marched there was more of a police presence. But even he was hit by a rock and some of my photos show that.

Do you ever regret leaving your camera behind when the events of Marquette Park happened?

I always regret leaving my camera behind, because the same thing happened in Selma, as well. I would have loved to have photographed [the marches] … but we were always told to never carry anything that could be construed as a weapon, even a finger nail file. It seems so absurd now but it wasn’t then.

What did your family think of your work especially after what happened at Marquette Park?

I was very fortunate to have the support of my family. I grew up in a virtually all white community. We didn’t grow up thinking about these race issues. I am embarrassed to say, but I was very naïve, and they were as well, but they supported me and everything that I did. That was very helpful.

The 48th anniversary of Marquette Park is coming up on Aug. 5. Your thoughts on that day?

I think what’s sad is that many of the issues Dr. King addressed then, are still with us today. For instance, there’s still rental discrimination, sales discrimination, lending discrimination — it’s still going on.

How do you keep yourself from getting discouraged?

I am discouraged; it’s too late for that. As I mentioned earlier I was very naive back then. When we were in Selma I really thought there was more we could do. Certainly there’s been change but we still have a long way to go.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

As you can see from my photographs I was very close to Dr. King. Today I have many more lenses; but I didn’t at the time. So I was very close to him, but I never met Dr. King. When I was photographing him, there was so much going on and at times there were pretty scary circumstances. I never felt like I could just walk up to him and say, ”Hi Dr. King, you don’t know me…” I always thought, well, I can’t meet him today, I can meet him tomorrow. And at some point tomorrow never came.

What do you hope people will think of when they look at your photographs, especially what you documented of the 1960s?

When people look at my photographs I want them to look back and remember what so many people have gone through. But I don’t want them to stop at that. I want them to look ahead. I want them to think of what they could do now.

Each one of us can make a difference. There’s so much work left to do and so much left undone we just have to get busy and keep working at it.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.